...a stone, a leaf, an unfound

door; of a stone, a leaf, a door. And of all the forgotten faces.

Naked and alone we came into exile.

In her dark womb we did not know our mother's face; from the

prison of her flesh have we come into the unspeakable and incommunicable

prison of this earth.

Which of us has known his brother?

Which of us has looked into his father's heart? Which of us has

not remained forever prison-pent? Which of us is not forever

a stranger and alone?

O waste of loss, in the hot mazes,

lost, among bright stars on this most weary unbright cinder,

lost! Remembering speechlessly we seek the great forgotten language,

the lost lane-end into heaven, a stone, a leaf, an unfound door.

Where? When?

Strange mad book! Character-drawing

dreadful. No sense of form--and yet a strangely wonderful book.

"The seed of our destruction will blossom in the desert, the alexin of our cure grows by a mountain rock, and our lives are haunted by a Georgia slattern, because a London cutpurse went unhung. Each moment is the fruit of forty thousand years. The minute-winning days, like flies, buzz home to death, and every moment is a window on all time."

Oliver Gant--the father, sculptor, wandering until he came to Altamont, there to marry Eliza Pentland. These characters are never convincing from start to finish, nor is any other character. They are all drawn in fits and starts of rhetoric and contradiction. Unless it be supposed that the types or living personages from whom they are drawn are mad, they have no reference to reality. Not even the Eugene Gant, hero of the story, obvious idealized picture of the author, seems a wholly real character. The story traces the growth of Eugene Gant through the maze of mad emotions and fierce, unprepared explosions of hatred, love, violence, etc. that make up the Gant family life. Ben, Steve, Helen, Luke, and one who died young make up the family.

Eugene's growth, paper-boy, private school, state university. The book culminates in Ben's death--which is peculiarly effective but scarcely because of our interest in Ben's character. Here the great defect of the author is apparent. Ben's character had been drawn for us spasmodically. We had no full or consistent picture of it. Indeed, the actions of most of the characters are unpredictable in ever[y] respect--except that they may be counted upon to be unpredictable.

The boy Eugene, by an average judgment, would be accounted mad. Not because of the general brilliancy and strange imaginativeness of his behavior--beating his head against a wall, breaking into savage laughter.

Other defects--lack of humor--almost complete--although it is quite obvious that the author imagines that he has a most delicate and broad humor.

The book is marred by an insufferable egotism. It is so obvious that the thing is autobiographical that we cannot but read the author's opinion of himself into every description of Eugene. This egotism is not to be objected to in itself, but for what it does to the author's artistry and his feeling for existence. It cannot be said that the Eugene Gant of the story felt any real love for anyone but himself. The love scenes of the book, whether for girls or members of the family, are all violent and unnatural, sudden, unconvincing. It does not seem to me that any character anywhere in the book is motivated by a real feeling of love. I think that this must have grown out of the strange, pathological subjectivism and egotism that was Thomas Wolfe's. He was certainly and clearly a genius in the ordinary acceptation of that word--but he is so by his strangeness and not by naturalness or real understanding and feeling for existence.

In one respect, however, and herein I think

resides the great strength of the book, the author captures a

certain greatness--it is his feeling for this exile on the earth

and the anchorless soul, wandering, grieved and adrift--such

as he expresses in the proem. He returns with real poetic feeling

and passion and metaphysical intuition to this theme again and

again. When, as he occasionally does, this feeling is suggested

in the characters ordinary, and the dreary richness of the style

and the unnatural images of people are at once compensated for.

_________

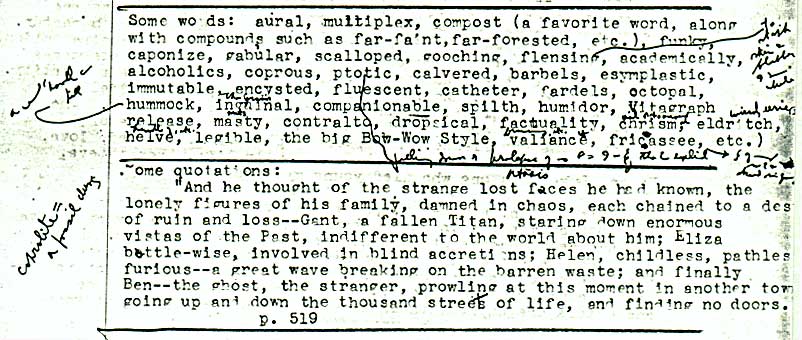

Some words: aural, multiplex, compost (a favorite word, along

with compounds such as far-faint, far-forested, etc.), funky,

caponized, gabular, scalloped, gooching, flensing, academically,

alcoholics, coprous, ptotic, calvered, barbels, esymplastic,

immutable, encysted, fluescent, catheter, fardels, octopal, hummock,

inquinal, companionable, spilth, humidor, vitagraph release,

masty, contralto, dropsical, factuality, chrism, eldritch, helve,

legible, the big Bow-Wow Style, valiance, fricassee, etc.)

_________

Some quotations:

"And he thought of the strange

lost faces he had known, the lonely figures of his family, damned

in chaos, each chained to a des[--?] of ruin and loss--Gant,

a fallen Titan, staring down enormous vistas of the Past, indifferent

to the world about him; Eliza battle-wise, involved in blind

accretions; Helen, childless, pathless [,?] furious--a great

wave breaking on the barren waste; and finally Ben--the ghost,

the stranger, prowling at this moment in another town [,?] going

up and down the thousand streets of life, and finding no doors.

p. 519

_________

"His face was thin and bright

as a blade, below the great curling shock of his hair; his body

as lean as a starved cat's; his eyes bright and fierce.

O sea! (he thought) I am the hill-born,

the prison-pent, the ghost, the stranger, and I walk here at

your side. O sea, I am lonely like you, I am strange and far

like you, I am sorrowful like you; my brain, my heart, my life,

like yours, have touched strange shores. You are like a woman

lying below yourself on the coral floor. You are an immense and

fruitful woman with vast thin thighs and a great thick mop of

curling woman's hair floating like green moss above your belly.

And you will bring me to the happy land, you will wash me to

glory in bright ships."

_________

...and casting the fierce sword of his glance with utter and

final comprehension upon the room haunted with its gray pageantry

of cheap loves and dull consciences and on all those uncertain

mummers of waste and confusion fading now from the bright window

of his eyes, he passed instantly, scornful and unafraid, as he

had lived, into the shades of death.

We can believe in the nothingness

of life, we can believe in the nothingness of death and of life

after death--but who can believe in the nothingness of Ben, Like

Apollo, who did his penance with broken feet, into the gray hovel

of his world. And he lived here a stranger, trying to recapture

the music of the lost world, trying to recall the great forgotten

language, the lost faces, the stone, the leaf, the door."

_________

p. 562--an interesting metrical recurrent theme in the realistic

scene. Old Fatty Pert mourning Ben along with Eugene at the cemetery.

It was October....

It was October, but some birds

were waking. ...

It was October, and the leaves

were shaking. ...

In that enormous silence, birds were waking. It was October,

but some birds were waking.

(Somewherein between ther)

Wind pressed the boughs, the withered

leaves were quaking.

_________

The last scene, suggests a quality

in the book allied to that above, and characteristic of Wolfe,

a sense for the time that is gone. Not so much a sense of time

in all its mysteriousness, future, present, and eternity--but

rather time that is gone--the ghost residence of the dead events.

He expresses this singularly well, better than any author I have

yet read.

_________

The scene describes an imag. meeting at night with dead Ben on

the city Square.

"And through the Square,

unwoven from lost time, the fierce bright horde of Ben spun in

and out of its deathless loom. Ben, in a thousand moments, walked

the Square: Ben of the lost years, the forgotten days, the unremembered

hours; prowled by the moonlit facades; vanished, returned, left

and rejoined himself, was one and many--deathless Ben in search

of the lost dead lusts, the finished enterprise, the unfound

door--unchanging Ben multiplying himself in form, by all the

brick facades entering and coming out.

And as Eugene watched the army

of himself and Ben, which were not ghosts, and which were lost,

he saw himself--his son, his boy, his lost and virgin flesh--come

over past the fountain, leaning against the loaded canvas bag,

and walking down with rapid crippled stride past Gant's toward

Niggertown in young pre-natal dawn. And as he passed the porch

where he sat watching, he saw the lost child-face listening for

the far-forested horn-note, the speechless almost captured pass

word. The fast boy-hands folded the fresh sheets, but the fabulous

lost face went by, steeped in its incantations."

(A good example of Wolfe's power of evocation, ghostlike, and his absorption in a nostalgic mood of self-remembrance.)

"He stood naked and alone in darkness,

far from the lost world of the streets and faces; he stood upon

the ramparts of his soul, the far interior music of the horns.

The last voyage, the longest, the best.

"O sudden and impalpable faun, lost in the thickets of myself,

I will hunt you down until you cease to haunt my eyes with hunger.

I heard your foot-falls in the desert, I saw your shadow in our

buried cities, I heard your laughter running down a million streets,

but I did not find you there. And no leaf hangs for me in the

forest; I shall [?lift] no stone upon the hills; I shall find

no door in any city. But in the city of myself, upon the continent

of my soul, I may enter, and music strange as any ever sounded;

I shall hunt you, ghost, along the labyrinthine ways until--until?

O Ben, my ghost, an answer?"

_________

An example in this of Wolfe at his best and his worst. The odd,

mystical, half-suggesti[o]ns, the metaphysical implications,

the terrible crippled artistry--for example, in this belated

suggestion that Ben is the ghost of his own soul--good in a way--but

so badly prepared for.

_________

The Story of a Novel

by Thomas Wolfe,

As it first appeared in 1935, December,

in The Saturday Review of Literature.

An account of his creation of the first two

novels and his methods of composition. Very illuminating. ...

Tells how Wolfe went about writing

his first book, published in 1929, when he was 29. His method

of composition, his theories of writing, etc. The cutting of

his gigantic manuscripts, etc.

| The Novel | Essays | Other Writings | RL Jr. Writer's Award | Complete Contents | Book Orders |

| The Biography | Photos / Postcards | RC Source & Facsimiles | Suicide & Prevention | Movie & Score |