Selected Writings From Raintree County The Reverend Lloyd G. Jarvey --Ten Passages-- Ross Lockridge, Jr.,

Raintree County, 1948

Epigraphs

Beyond this map, the earth dissolved into a whole republic of such linear nets, all beaded with human lives. Then all these lines dissolved, and there--without north, south, east or west--was the casual republic of the Great Swamp, a nation of flowers black and white, brown and red and yellow.

p. 357~ --I will never be converted again, Brother Jarvey.

Esther Shawnessy, p. 361~ The time had come to destroy this disobedient world and its multiplying eyes.

Reverend Jarvey tormented by a vision of profane love, p. 576~ Returning, Mrs. Passifee had a stone jug from the earth-cellar. Clear yellow wine guggled from stone lips. She filled two glass tumblers.

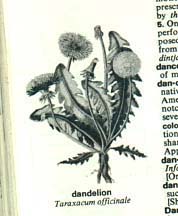

--Just a little dandelion wine, she said. Practickly no alcohol in it. It'll cool you off. If you don't mind.

For answer, Preacher Jarvey leaned forward, picked up a tumbler, drained it.

He leaned back again and closed his eyes. There was a sharp sweet taste in his throat, of summer lawns, of the sunwarm faces of dandelions.

p. 582~ --Lord, you have placed this poor weak woman in my arms, Preacher Jarvey said. What shall I do with her?

--Just go on and pray as hard as you want, Brother Jarvey. My daughter Libby's down at the school and nobody'll bother us.

p. 585~ . . . The evil ones had been defeated by their own evil.

p. 1009

Passages

pp. 355-6

--SEVEN TIMES,

the Senator said. Laugh if you will, gentlemen, but back in those

days I was a brute of a boy.

Somewhere down the street a boy

touched off a cannoncracker. Mr. Shawnessy jumped, felt unhappy.

The Senator was approached by delegates of the Sitting and Sewing

Society, whose hands he pumped for a while.

--I used to pull a pretty mean

oar myself, the Perfessor said. By the way, John, what is that

godawful yelling over there?

For some time, a great voice had

been booming over the trees, getting louder and angrier. Now

and then a stentorian shout soared above the rest, grating hoarsely

like a horn blown too high and too hard.

--That's God, Mr. Shawnessy said.

--What? said the Perfessor, crossing

himself. Is he here today too?

--It's the Revival preacher, fellow

named Jarvey. One of these Kentucky evangelists. He confuses

himself with the Deity--and understandably, too, if you saw him.

From June to August, he's the most powerful man in Raintree County.

The ladies come back every year to get converted all over again.

He's been pitching his tabernacle on the National Road here for

the last three summers. No one knows just why. When I first came

to Waycross in the summer of 1890, he was already here. Your

little friend, Mrs. Evelina Brown, has been very friendly with

him. She considers him a magnificent primitive personality, which

in a way he is.

--That's just like Evelina, the

Perfessor said. Like all thoroughly erotic women, she begins

by falsifying an aesthetic type. I hope it didn't go any farther

than that. Where does he go for the winter?

--Nobody knows. Back to the Kentucky

mountains, I suppose, after restoring heaven to the local souls.

--I suppose like all these Southern

ranters he's a goat in shepherd's clothing.

--So far he's escaped criticism

of that kind, even though he's a bachelor. But he's a brutal

converter. Built like a blacksmith, he brandishes his great arms

and beats the ladies prone. He has a great shout that scares

everybody into the arms of Jesus. You ought to hear him.

--I do hear him, goddamn him, the

Perfessor said.

--Still he's a man of God, Mr.

Shawnessy said resignedly. My own wife regularly attends his

revival meetings. She's over there now. ....

pp. 356-66

The big voice

a quarter of a mile away shot up in a high wail and came down

with a snarling crash. Mr. Shawnessy felt vaguely insecure and

unserene.

He saw the fabric of his life a

moment spread out like a map of interwoven lines. Across this

map trailed a single curving line, passing through its many intersections.

Source and sink, spring and lake existed all at once. One had

to pass by the three mounds and the Indian Battleground to arrive

at the great south bend. One had to pass by the graveyard and

the vanished town of Danwebster to reach the lake. And one had

been hunting the source all one's life. The forgotten and perhaps

mythical tree still shed its golden petals by the lake.

Beyond this map, the earth dissolved

into a whole republic of such linear nets, all beaded with human

lives. Then all these lines dissolved, and there--without north,

south, east or west--was the casual republic of the Great Swamp,

a nation of flowers black and white, brown and red and yellow.

We were great men in our youth.

It was one life and the only. We strove like gods. We loved--and

were fated to sorrow. But from our striving and from our sorrow

we fashioned

REV. LLOYD G. JARVEY, Officiating

ESTHER ROOT

SHAWNESSY, returning from the Station, walked to a place midway

in the tent and sat down. She looked around, but Pa wasn't there.

His shiny buggy and fast black trotter weren't among the many

vehicles parked along the road. Pa had been coming regularly

to the revival meetings, since the Reverend Jarvey had converted

him a few weeks ago. He would sit in a back seat, and after nearly

every meeting, he had come up and said,

--How are you, Esther?

--Just fine, Pa.

--The old home is waitin', Esther.

You can come and visit any time.

--As soon as I can bring Mr. Shawnessy

and the children, I'll be glad to come back, Pa.

Pa would bow his head slightly

and kiss her cheek and drive away.

Years ago, not long after Esther

had left the Farm, Pa had taken a second wife and had begot nine

children upon her before she died. Nevertheless Esther thought

of Pa as being alone in that now nevervisited part of the County.

As for her, whenever she saw him, she had the feeling that Pa

still had the power to take her back, though she was thirty-five

years old and had three children.

The tent now filled rapidly as

the excitement over the Senator's arrival subsided. A great many

people who wished to remain in Waycross for the Patriotic Program

in the afternoon dropped in for the revival service, not a few

attracted by the fame of the Reverend Lloyd G. Jarvey.

Sitting under the vast foursided

tent, the crowd watched the little tent adjoining in which the

preacher customarily remained in prayer and meditation until

the hour for the service. The flap of this tent was closed. A

murmur of expectation ran through the revival crowd. Two ladies

were talking in the row behind Esther.

--Do you think he'll turn loose

and convert today?

--I don't reckon he will. He'll

just preach. I hear he converted a hundred people last Thursday.

They say he converted one a minute after he got started.

--He converted me two Sundays ago.

I didn't think he could do it, but he done it.

--Where'd he convert you, Fanny?

Big tent or little tent?

--He converted me in the little

tent. All the women said it was better that way. They said in

the little tent it was harder to resist the Lord. They said to

go around after service, and if he wasn't too tired he'd convert

you.

--I like it better that way. More

private-like.

--When I said I didn't like to

do it in front of everyone, they kept tellin' me to go and do

it in the little tent. I kept sayin' no, I didn't feel like it.

I didn't know if I was ready to let Jesus come into my heart.

Finely one night I waited around after service, and nearly everybody

was gone, and he was still in the little tent and the flap down.

I was terrible skeered. Finely I felt the spirit in me just a

little bit, and I went up and raised the flap a little. He was

in there all right, convertin' Lorena Passifee.

--Lorena Passifee! I thought he

converted her last summer. In the big tent.

--He did, but I guess she slipped.

--She slipped all right. How'd

he convert her?

--It was real good. When I raised

the flap, Lorena was on her knees, moanin'. I'm a sinner! she

yells. Hosanna! he yells, and he laid her flat on her back and

converted her right before my eyes. He did the layin' on of hands,

and he shook her to let the spirit of the Lord come in. She was

like a ragdoll in his arms.

--Lorena's a big woman too.

--I know that, but she was like

a ragdoll when he shook her. Then he saw me, and he broke right

off as courteous as you please. I'll come to you directly, Sister,

he says. Just wait outside. I waited, and pretty soon Lorena

come out of there lookin' all shook to pieces. I was that skeered

I could hardly move. Come on in, Sister, he yells in that big

voice of hisn. God's waitin' for you. Don't keep God waitin'!

I went in, and from then on I hardly knowed what happened to

me. I kept throwin' my arms around and pretty soon, he picked

me up and shoved me right up in the air as if I was goin' straight

to Jesus. I never felt such strength in anybody's arms. Take

her, Jesus! he yells. Jesus, she wants to come to you. Zion!

I yelled. Then all of a sudden down he brung me and flat on my

back, and the first thing I know I'm proclaimin' my sins and

acceptin' the Lord, and he converted me.

--He sure works you up. He converted

me two summers ago and agin last summer. Mine was both little

tent ones. Ain't he the most powerful man!

--But it's too bad about his weak

eyes.

--Has he got weak eyes?

--They say he's blind with his

glasses off.

--I just love to watch him convert.

June, they say he converted the whole Sitting and Sewing Society

three weeks ago in one afternoon.

--I believe I'll have to let him

convert me again, June said thoughtfully.

Esther was remembering Preacher

Jarvey's attempt to convert her. Two summers ago, she had gone

one day after a Sunday morning service to see him about a program

of the Ladies' Christian Reformers. He was alone in the little

tent.

--Come on in, Sister Shawnessy.

While she was explaining her mission,

he had peered down at her queerly--he didn't have his glasses

on. Suddenly he had caught her hands.

--Sister, I feel the presence of

the Lord in this tent.

--well, I hope so, Brother Jarvey.

She allowed him to hold her hands.

Men of God had always seemed to Esther an elect breed, with peculiar

privileges.

--Sister Shawnessy, have you been

converted?

--O, yes, Brother Jarvey.

In fact, her conversion at age

sixteen had been a dreadful and exhausting experience. She had

been broken up for days before and after. She never expected

to be converted again, and didn't understand people who got converted

over and over.

--Sister Shawnessy, I think you

ought to get converted again. I think you ought to let the sweet

light of Christ to shine on your soul again. Sister, I feel that

we are both bathed and beautified by the radiant presence of

Jesus at this very moment.

--I will never be converted again,

Brother Jarvey.

--Let us pray! Preacher Jarvey

had shouted. Down on your knees, Sister. The Lord is comin'.

Obediently, she had gone to her

knees and had placed her hands in the attitude of prayer. Brother

Jarvey had then prayed with wonderful fervor for half an hour,

exhorting the kneeling sister to search her heart out for all

impurities, to consider well whether or not she was entirely

pure and perfect for God's kingdom.

She had repeated with infinite

patience that she didn't consider herself perfect--no one in

this mortal sphere, Brother Jarvey, was perfect except her husband,

Mr. Shawnessy--but she had never once swayed from the teachings

of Christ, at least since her conversion. It had seemed to her

that it would be a blasphemy to the memory of it, the second

greatest experience she had known, if she let herself be converted

again.

But Brother Jarvey was not easily

put off. He had persisted with a force that she would have deemed

brutal except for the holy purpose behind it. He exhorted and

sweated. When everything else had failed, he finally resorted

to his godshout.

--Go-o-o-o-o-o-d, he yelled suddenly,

his voice attaining a trumpet pitch of exultation, grating hoarse

like a horn blown too hard.

His powerful body shot straight

up with the cry, towering above her. He prolonged the shout on

a high pitch and then came screaming down:

--is here!

This treatment could be repeated

as many times as necessary. But usually one godshout was enough.

Most of the ladies caved in and allowed themselves to be thrown

bodily to Jesus. But Esther had continued quietly in her attitude

of prayer through six successive godshouts, each more triumphant

than the last.

After his failure to convert her

in the little tent, Esther had observed a coolness toward her

in Preacher Jarvey, even though she had been most helpful to

him in his work and had attended the services regularly.

Her experience was not typical.

As far as she knew, only one other woman in the County had been

able to resist that thundering call to Christ. Mrs. Evelina Brown

had held out too, though for different reasons. She was a freethinker,

and though she was very much interested in Preacher Jarvey as

a personality, she didn't believe in the Christian religion.

Nevertheless, she had often gone for talks with the Preacher

in the little tent, and he had made mighty efforts to convert

her. He had spent hours discussing theology with her, a field

of knowledge in which he had a surprisingly deep learning. Preacher

Jarvey had publicly remarked that the abiding heresy of Mrs.

Brown was the greatest sorrow of his life. Mrs. Brown had privately

remarked that she had once lived through twelve godshouts without

capitulating.

The highpoint of a revival service

in the big tent came when Preacher Jarvey finally unwound and

let his voice hit the sky with the godshout. The longer he postponed

it, the more devastating it was.

--Go-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-d is here!

With that tremendous cry, he unleashed

the thunderblast of divinity on the unshriven sheep, and down

they came in flocks trembling to the altar.

--I sort of hope he'll turn loose

this morning, one of the ladies in the back row remarked.

It seemed unlikely to Esther that

he would, but the Reverend Lloyd G. Jarvey wasn't easy to fathom.

It was after ten when without warning

the flap of the little tent flew up, and Preacher Jarvey appeared

in the opening, clad in a long black preacher's coat, reversed

white collar, tightfitting black pants and hookbuttoned black

shoes.

A man of perhaps forty, he stood

six feet tall, but seemed less because of his great shoulders

and arms. His head had a wild, lawless look; hair and beard made

one brown shag that nearly buried his ears and mouth. His brown

eyes were savagely restless under frowning brows. He had the

look of a huge, primitive god, poised on the brink of some tremendous

act.

Instead, he reached into the pocket

of his coat and took out a pair of spectacles, which he perched

on the bridge of his fleshy nose. All the forbidding grandeur

of his aspect was undone by the little thick round lenses, through

which the Reverend Lloyd G. Jarvey peered, a great strength imprisoned.

Now he walked under the flap of

the big tent and up the steps to the platform, leaning slightly

backward, heavily swinging his feet and arms but taking a rather

short stride for the effort involved.

Once behind the pulpit, he plucked

off the glasses. His brows unbent, and his face assumed a look

of majestic displeasure mingled with sorrow. He leaned his head

farther back. His eyes dosed. He paused.

The congregation became raptly

still.

--Let us pray.

The lips flapped slowly, as if

themselves immobile but moved by the action of the jaws. The

voice was a harsh baritone, monotonous and trumpeting, quavering

with sanctity. The Southern accent gave it a faintly barbaric

sound to Northern ears. The Preacher's language was a bastard

fruit produced by the grafting of Biblical phrase on the speech

of Southern hill people.

The introductory services passed

with prayer and hymn-singing. At length, Preacher Jarvey opened

the black Bible on the pulpit.

--Brothers and sisters, we are

celebratin' today in pomp and pride the birth of our Republic.

It's a beautiful day that God has given us to remember our beginnin's.

Look about you, and see what the Lord has given you. He has given

you this green and pleasant valley teemin' with all good things.

The trees drop their abundance on the earth. The kine return

at evenin' with full udders. The corn is as tall as the knee

of a virgin. It is a beautiful mornin', and the day is all before

you.

Beware! Holy and terrible is the

voice of the Lord. Beware! lest you hear His awful voice at evenin'

in the cool of the garden.

Brothers and sisters, on just such

a day as this did the father and mother of mankind wander in

that beautiful garden which God in His great beneficence bestowed

upon them. On just such a day as this they heard the sound of

the clear fountains flowin' with perpetual balm, and the voice

of the lion roarin' was like the bleat of a lamb. Alas, on just

such a day as this they sinned and knew not God and turned from

His teachin'.

On this great day of our national

beginnin's let us remember an older beginnin'. I come before

you today to remind you of the origin of mankind. If every word

made by man were lost and the first leaves of God's Book remained

to us, man would still know his sinful history and his sorrowful

heritage. The oldest story in the world is the story of the Creation

and the Fall of Man. Hit's a beautiful story, o, how beautiful

it is, for hit is full of the beauty and the terror of the Lord.

As he warmed to his subject, Preacher

Jarvey had spoken with longer cadences, the hoarse chant of his

voice achieving higher climaxes before the trumpeting doomfall

at end of sentence. Now he plucked the glasses from his pocket

and put them on his nose. His brows made their ferocious pucker

as he easily lifted the big pulpit Bible and held it close to

his eyes, his face hidden by the book.

--In the beginning, God created

the heaven and the earth.

Esther listened as the hoarse trumpet

of the voice behind the Bible blew on and on. She had often heard

these beautiful words, the oldest in the world; they were like

a language of her soul, telling her a forgotten legend of herself.

As she listened, images of her life in Raintree County crowded

through her mind, bathed in the primitive light of myth--pictures

of sorrow, love, division, anger.

--And the Lord God formed man

of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the

breath of life; and man became a living soul.

And the Lord God planted a garden

eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed.

And out of the ground made the

Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and

good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden,

and the tree of knowledge of good and evil.

Now, brothers and sisters, I ask

you to imagine this primitive garden in the midst of the earth,

bloomin' with the first freshness of creation upon it. How beautiful

is the garden before the great crime! Here the first man walks

in innocence. He knows not that frail defect called Woman.

Meanwhile, in the midst and middle

of this garden two trees are growin'. Some people say that they

were apple trees. Some people say that they were pomegranate

trees. The Bible does not say what they were. And the reason

why the Bible does not say what they were is that they were alone

of their kind. Those trees did not bear fruit for seed, after

the manner of natural trees. They had no name except the Biblical

name. One was the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, and

the other was the Tree of Life.

The Tree of the Knowledge of Good

and Evil--brothers and sisters, hit was no ordinary tree. Hit

was God's tree. Hit was many cubits thicker at the base than

the greatest natural oak. The bark of the tree, hit was a thick

scale. The leaves of the tree, they were broad and polished.

The fruit of the tree, hit was a scarlet cluster of sweetness,

burstin' with juice.

And what was that other tree like?

O, dearly beloved, the mind of man is not able to picture hit,

and the voice of man, hit is not able to declare hits kind. Hit

was called the Tree of Life, and hit grew in the darkest and

oldest part of the garden, guarded by dragons breathin' fire.

And the Lord God commanded the

man, saying, Of every tree of the garden thou mayest

freely eat:

But of the tree of the knowledge

of good and evil, thou shalt not eat of it: for in the

day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt

surely die.

Disturbed by the sound of a buggy

approaching, Esther looked up, but it was not Pa's buggy.

--And the Lord God caused a

deep sleep to fall upon Adam, and he slept: and he took one of

his ribs, and closed up the flesh instead thereof,

And the rib, which the Lord

God had taken from man, made he a woman, and ...

Under the great tent filled with

the trumpet of Preacher Jarvey's voice, Esther was sad, remembering

in a field back of the farmhouse. She was very close to the earth as if she had just come out of it. It had a brown soft look in the light, and the light was like early morning in the spring. The earth of the field had been freshly turned by the plow. The ribbed furrows seemed to spread from a point far off and come undulating toward her, widening and widening until they engulfed her where she stood, her bare feet pressed down into the earth.

pp. 371-3

--BODY and soul,

the Woman was made out of Man. Body and soul the Woman belongs

to Man, God made her to be Man's partner and helpmeet, and o,

sisters of the congregation, how woefully she betrayed His trust!

Preacher Jarvey shook his shaggy

head and bent his brows sternly against the good ladies of Raintree

County, who made up the major part of his audience.

--Now, let us consider this Woman.

In makin' her, God put a new thing into creation. He made a frail

defect. He did it with a purpose because the Lord God Jehovah

does everything with a purpose. He made it to try the Man, to

test him. And o, brothers of the congregation, how woefully Man

betrayed his Maker's trust!

But I am gettin' ahead of my story.

Now then, after the Lord made Woman, she wanders alone in the

garden. The shinin' of the sun of that eternal summer, which

is the only season of Paradise, shows her body to be without

all habiliment or shameful adornment. Sisters of the congregation,

she had no other garment than her innocence. God gave it to her,

and she needed no other.

The good ladies of Raintree County

shifted uneasily in their bustles and great skirts. They patted

their flouncy hats and poked at their twisted hair. Preacher

Jarvey's savage eyes glared displeasure on their finery. Then

his eyes became remote. He departed upon a point of pedantry.

--some depict the Mother of the

Race as wearin' a figleaf before the Fall. Fellow Christians,

this belief is in error. Hit is against Holy Writ. The Book tells

us that she was nekkid, and nekkid she was.

Behold her then, the first Woman,

cowerin' in the dust before her Father and her God. In that first

blindin' moment of existence, she recognizes on bended knee the

majesty and godhead of her Maker.

Esther followed a buggy with her

eyes as it approached from the direction of Moreland. It was

not Pa's buggy.

--Yes, the Woman knew her Father

before she knew her Husband. Then the old story tells us that

havin' made the Woman, the Lord brought her unto the Man. O,

sweet encounter! Brothers and sisters of the congregation, hit

is the dawn of love before Man knew Woman in carnal pastime.

They reach out their arms to each other, not knowin' that they

are the parents of mankind but only knowin' that the loneliness

of the garden has been overcome. Behold them standin' in

SOFT SPRING WEATHER

OF RAINTREE COUNTY BATHED HER

in warmth as she waited in the yard of the Stony Creek School on the last day of the school year.

pp. 575-9

In flagrante

delicto! Preacher Jarvey pacing restlessly in the tent was

tormented by the words. He saw them writhing on a ground of scarlet

flame, fiendishly alive, their heads darting and hissing. The

flames withdrawing disclosed two forms, a man and a woman naked,

turning round and round, their lips and hands and yearning limbs

touching and twining.

Preacher Jarvey walked with a rapider

stride. He was panting. His eyes glared viewlessly. A vision

of profane love tormented him with a whip of shrewd lust as often

it had when he lay at night waiting for sleep. In this vision,

a hated figure walked through Waycross in the hovering darkness,

looking covertly to left and right. Arriving at stately gates

east of town, it paused a moment, then darted into a contrived

garden that Preacher Jarvey himself had often passed but never

entered. And the sinful intruder glided stealthily past vague

balls of shrubbery on the lawn, reached a verandah prickly with

filigree, knocked stealthily at a door. And the door opened.

And the stealthy form was lost in the dark and scarlet depths

of a voluptuous mansion. In flagrante delicto!

--Hosanna! the Preacher panted

under his breath. The hour is here. Hosanna! Hit has come!

And suddenly he burst through the

tentflap.

The day was hostile with radiance,

walling him in with green and golden mist. He set out walking

toward the intersection. As he approached it, laughter, cries,

clangs, explosions enveloped him. Wheels and trampling hooves

threatened him. The lightfilled intersection of Waycross, which

had endeared itself to him by its visual simplicity (four beginnings

of streets losing themselves in peaceful summer), erupted with

strangeness.

The time had come to destroy this

disobedient world and its multiplying eyes.

The Preacher turned east at the

intersection. As he walked, he pulled out his watch and held

the face of it close to his own. Black hands and numerals swam

into the green globe of his vision and wavered there, enormously

precise. Eleven-thirty.

Hosanna! The hour had come!

Like sadness and tears, a traitorous

feeling surged up from the mist around him. The way here was

magical with soft anticipation. Many times in vanished summers

he had gone along this street in the late morning and had passed

Mrs. Evelina Brown on her morning walk into Waycross. Often and

often (for he had learned to depend upon the regularity of this

walk) his yearning eyes had plucked her from the oceanic void

of the increate and held her, softly writhing, flushed, exhaling

a mist of breath. He would exchange a few amenities with her,

as the godshout raged unuttered in his breast, and then reluctantly

he would let her gracious form slip once more into the stream

of the inactual.

The faces were a thinning stream.

The sidewalk ended. He plunged into golden heat. He was on the

empty road passing the Jacobs farm. He looked neither to right

nor left. He wouldn't stop at the Widow Passifee's, despite his

promise to Brother Gideon Root. He would go on past. Hosanna!

The hour had come!

Suddenly, he was aware of someone

approaching in the white roadway, coming closer and closer to

the minute pebbles and brown dust on which he walked. The black

twisting shape stood suddenly before him like a jinnee in a glass

bottle, writhing, fantastic, dreadful. The creature was incredibly

tall and thin, black eyes stabbing through pince-nez glasses,

face long, lined, grinning with malice and amusement. It made

a ceremonious bow, leaning on a cane. A thin tongue of derision

licked its hissing lips.

--Have I by chance the honor of

addressing the Reverend Lloyd G. Jarvey?

--You have, Brother! Praise the

Lord!

The words were hurled like an accusation,

quavering and frustrate.

--Praise the Lord! shouted the

intruder in a highpitched, nasal voice crackling with sanctimony.

Pleased to meet you, Brother.

--Who might you be, Brother?

--A visiting preacher, Brother,

the thin intruder said. The Reverend Jerusalem Webster Stiles

from New York.

--Pleased to meet you, Brother.

He bowed his head and fairly butted

his way past this hateful rival.

--One moment, Brother. What is

the status of sin these days in Raintree County? Enough to go

around, I trust?

A malicious, cackling laugh pursued

him as he went on. Confusion warred with rage. Someone had set

this foreign dog upon him.

Nevertheless, he went by the Widow

Passifee's and continued until he saw the blurred lines of an

iron fence on his left. He slowed down, panting as though he

had been running. He listened. His ears cropping from the shaggy

brown hair were sickly sensitive to every sound, but there were

no footsteps on the road. He walked slowly to the iron gates.

They stood open, the ironwork designs drawn on his vision with

painful exactness, while beyond them a brown walk faded into

a lake of green.

He stopped. He had come to a threshold

of decision.

Yes, the time had come. Perhaps

he might forestall God's vengeance by an act of loving kindness.

Wasn't this woman after all the one most worthy to be saved?

Who but Lloyd G. Jarvey, he that had been called the Blind and

had been blessed with vision, he that had killed and ravaged

in his great hill-strength, who but he was chosen to tame this

sophisticate daughter and teach her submission, even in the chambers

of her scarlet palace?

My daughter, had you forgotten

your God? What have you been doing in my absence, my loving daughter?

Did you suppose that I did not foresee this invention, that I

was incapable of this pleasant pastime of mortals? Erring and

beautiful daughter, God is able to do anything, possesseth every

power and pleasure. In one of my earlier shapes, when I was several

and not one, I too was Begetter. But I had forgotten this earlier

self, until you reminded me of it. You discovered it without

permission, my intuitive daughter. You entertained false forms

of myself, obsolete deities, in this garden which I gave you

to tend. And should you not therefore endure the chastisement

of a jealous God?

The Reverend Lloyd G. Jarvey walked

through the gate, heavyfooted, his powerful arms not swinging

at his sides, but slightly lifted as if appealing. His eyes in

the thick glasses had a fixed expression.

But then I am not wholly displeased

with you, my daughter. You have reminded me of myself. And what

if I should now return, and forgiving you for this evil knowledge

that you have acquired, should supplant your mortal lover, and

in my infinite power and mercy, take back to my own breast the

erring daughter?

Only for God and the gods, the

most beautiful mortals.

And if then I should find you here

hiding in the garden and hugely should come upon you, and you

should stand before me with eyes averted, beseeching my forgiveness

and admitting your guilt, and you should stand before me in the

stolen garments (but I know your white flanks and the little

applefirm. breasts tilted for love), then might there not be

for you a majestic revealing of Godhead? Then, o, then, might

there not be for you the hard, bluff strut and the bullgreat

weight of...

Preacher Jarvey was standing at

the base of the brick house. He saw clearly the clumps of columns

supporting the roof of the verandah, and beyond that a dull red

mass of walls. He breathed heavily; his breast swelled up as

if it would burst with the anguish of a wish that had no name.

This wish tore him with fury and anger; he opened his mouth as

if to give voice to it.

A sound pierced his ears, at first

muted and reedy, then swelling to a trumpet blast and ending

in a harsh wait of amorous fury. Male laughter volleyed. Feet

scuffled. A gate creaked.

In confusion, Preacher Jarvey turned

and ran. Along the path of his flight the garden started into

life around him. Naked women with sightless eyes stood suddenly

from nooks of shrubbery. Blurred shapes of bulls, archers, chariots

formed and faded on waves of lawn.

Harried by scurrilous laughter

and scuffling feet, he ran through the gates and stopped in the

road. The noises had lessened to a murmur. He peered at the garden

from which he had just been driven in confusion. What had he

come to do there?

Once more dull fury burned in his

chest. Against the old walls of his blindness a thousand stridulous

noises beat, surf of an oceanic world beyond his grasp. He was

sad as never before. His breath labored. The hot sun smote him

without mercy. He knew the anguish and sorrow of the one god

who may not be loving of beautiful mortals.

Now he held his eyes up to the

yellow light that blazed directly above him. It entered him with

splendor, destroying all vision but itself. It poured hot gold

and frenzy into his breast. He staggered west, incarnate with

a radiant god....

--Jupiter is his name, Mr. Jacobs said in answer to the Senator's question. Won first prize at the State Fair last year.

pp. 581-6

Rear protrudent,

the Widow Passifee was at the back of her yard, cutting away

a load of flowers with her yardshears. Colossally voluptuous

in a white dress, she bulged silently on Preacher Jarvey's vitreous

world still stricken with the sun.

Mrs. Passifce's yard had none of

the studied formality of Mrs. Brown's. It was tangled and frenzied.

The old picket fence surrounding her little frame house sagged

with unpruned vines. The outhouse behind was both visible and

odorous.

--Sister Passifee.

She squealed and whirled.

--Brother Jarvey! You plumb frightened

me.

He glared fixedly at her broad,

heartshaped face, green eyes, young wide mouth, small pointed

chin. She was flushed in the noonheat. Her neck and the white

roots of her breasts were shining with sweat. Her arms were full

of torn flowers.

--Won't you come in, Brother Jarvey?

--I will, Sister, I will.

He followed her into the dark cool

parlor. She started to put up the shades, which were drawn to

within a few inches of the sills.

--just leave them drawn, Sister.

The light hurts my eyes.

He sat on a horsehair sofa and

closed his eyes. Instantly, his inward vision swam with golden

splendors, splintering afterimage of the sun. Women with great

white glowing limbs and golden hair stood in nooks of green,

twisting ropes of flowers.

--Make yourself to home, Brother

Jarvey. It's hot, ain't it?

--It is, Sister.

She bit her lip and studied the

floor with a frown.

--Maybe you'd like a little refreshment.

To cool you off.

--As you please, Sister.

A waning gold gilded a garden of

clipped lawns, beds of tossing flowers. Flinging their golden

hair, whitebodied, with musical cries, the bare nymphs ran.

Returning, Mrs. Passifee had a

stone jug from the earth-cellar. Clear yellow wine guggled from

stone lips. She filled two glass tumblers.

--Just a little dandelion wine,

she said. Practickly no alcohol in it. It'll cool you off. If

you don't mind.

For answer, Preacher Jarvey leaned

forward, picked up a tumbler, drained it.

He leaned back again and closed

his eyes. There was a sharp sweet taste in his throat, of summer

lawns, of the sunwarm faces of dandelions.

--Goodness! Mrs. Passifee said.

You drink fast, Brother Jarvey.

Giggling nervously, she filled

up his glass on a little table beside the sofa and then sitting

down beside him sipped at her own.

--It is good, she said. A body's

a right to a little nip now and then on a hot day, don't you

think?

For answer, Preacher Jarvey leaned

forward, picked up his tumbler, drained it.

--Goodness! Mrs. Passifee said,

filling it up again.

She studied her glass.

--I got news, Brother Jarvey, she

said. I mean about him and her. Something that happened last

night. Be perfectly frank, I don't think we had much to go on

before. But if you really mean to accuse 'em of sinnin' together

tonight, why, I seen something that will int'rest you.

--Sister, he said. You may speak

to me without reservation. Don't let your feminine delicacy prevent

you from givin' a full story of what you saw.

--Well, she said, putting down

her glass, he come past here about seven o'clock in the evening,

and he had a sheaf of papers in his hand. He turned in at the

gate there and went up to her house. I could see plain from the

corner of my yard.

--Yes, the Preacher said.

A sweet sadness throbbed in his

veins. Sipping the cool wine, he leaned back and shut his eyes.

Blood of the dandelion drenched his throat.

--He went up to the house there,

and they was there all evening. I come out to my gate again and

again, and I knowed he hadn't left. They was no one else in or

out of that there gate all evening. They was hardly any light

at all in the house--I know because I walked down the road once

to see more clearer, and they was only a little low light burnin'

in a front room. I says to myself, I bet I know what's a-goin'

on in there.

Preacher Jarvey felt his hand squeezed.

He opened his eyes. The Widow Passifee was talking fast. Strands

of loose yellow hair had fallen around her heatflushed cheeks.

Her eyes glittered, and her wide young mouth made sounds that

were husky and musical.

--Of course, I hadn't no proof

of it, she said. Just what I suspicioned. But a course I never

dreamed what was a-goin' to happen.

Well, it was about eleven o'clock

at night, time for any selfrespectin' body to be in bed, and

I crept up to her fence and got in among some sumac bushes that

was right by the fence so's I could have a good view of the house.

I was even figgerin' maybe I might climb over and see if I could

have a real good see. I guess curiosity got the better of me.

But just then, I heard their voices, and the front screen opened

and shut, and here come Mr. Shawnessy walkin' down off the porch,

he never looked back once but just went right down the path and

out into the road and toward town. I was just about to climb

out a there and go home myself when I seen it.

The Preacher filled his own glass

and the Widow's from the jug. Heartshaped, the wide face of Mrs.

Passifee was very close to his own. His thick lenses were washed

with yellow waves of light. He watched her soft mouth trembling

with excitement.

--Go on, Sister, he said.

--So then there I was ready to

go, when all a sudden I heard the screen door open again--mind

you it wasn't ten minutes after he'd left--and all a sudden here

she come right down the steps of the verandah and out on

the lawn. Well, she was nekkid as the day she was born. Her hair

was all let down. The woman's plumb crazy, I said to myself.

--Praise the Lord! the Reverend

said. Go on, Sister.

--She was just a little slim thing,

hardly nothin' to her, compared to a woman like me. Well, she

took out and begun to run around the lawn and to throw back her

head and dance. She went here and there all over the yard and

threw up her arms, never sayin' a word or makin' a sound. It

was warm or she'd a caught her death a cold. After a while she

run to that there fountain down in front a the house where them

two nekkid children is and stepped right down into it. She's

goin' to drownd herself, I says. But no, not her. She puts her

face right up in the spray a the fountain and stood right there

and let the water run over her nekkid body. She looked jist like

a statue, Reverend, white and still in the starlight. There I

was--not more'n twenty feet away, a-layin' there sweatin' and

scared I was goin' to make a noise. It was so close I could see

a birthmark she had on her body. Then she ran out on the grass

again, her body a-shinin' from the water, and she run and threw

herself on the grass and rolled back and forth like a child,

and then she begun to cry or laugh, I couldn't tell which, and

then there was some kind of a noise from that field next to her

place where Bill Jacobs keeps that big bull a hisn, and she heard

it, and she jumped up and run like she was shot up to the house

and went in.

--Sister Passifee, lust is a dreadful

thing! O, hit is a terrible thing! Praise the Lord!

--Praise the Lord! Sister Passifee

said, sipping thoughtfully at her glass and allowing the Preacher

to squeeze her hand.

--Sister, the Lord means for us

to chastise these errin' creatures. But let us not be too hard

on them, Sister. Judge not that ye be not judged. A man may be

tempted by too much beauty, Sister, and the Devil may rise in

him. Alas, I have known what it is to sin, Sister.

--Me, too, Sister Passifee said,

sipping thoughtfully. More wine, Brother Jarvey?

Brother Jarvey's eyes were closed.

He was beginning to wag his big head. His voice had become loud

like a horn, monotonously chanting.

--Let us pray for these sinners.

They were sore tempted, Sister, and they sinned. Down on your

knees, Sister. Hosanna!

--Hosanna, Sister Passifee said,

obediently going to her knees. Maybe you can't blame 'em too

much. Sometimes it's pretty hard to resist the Devil.

--Let us pray, Sister, the Reverend

said, dropping to his knees before her and winding his arms around

her.

Sister Passifee nestled meekly

in his embrace.

--Lord, you have placed this poor

weak woman in my arms, Preacher Jarvey said. What shall I do

with her?

--Just go on and pray as hard as

you want, Brother Jarvey. My daughter Libby's down at the school

and nobody'll bother us.

--I lift up my eyes unto thy hills,

O Zion, he shouted.

His eyes, opening, perceived the

triumphant twin thrust of Sister Passifee's bosom in the white

dress.

He felt a momentary sadness that

left him stranded and deprived of strength. He waited. Thin sap

of the earth smitten into bloom by the sun flowed in his veins,

a soft fire. He closed his eyes.

An island of white sands and trees

darkfronded enclosed his vision. A tall stone column stood in

Cretan groves, and the young women gathered at the base to pelt

the shaft with petals. Light hands and flowery lips made adoration

and ecstasy at the base of the column in Crete.

The hour has come. Lo! it is here!

Now I will prepare for the feast. I will make myself known unto

you. It is the joyous noon, and the celebrants dash flowers and

wine on each other's faces. Naked, they run on Cretan lawns.

They do not know that the god himself is waiting in a green wood.

His large savage eyes have selected the whitest of the nymphs,

whose lips are wet with the wine of festival. He shrugs and lowers

his wrinkled front, the loose folds of his breast are shaken

with desire. He rakes the ground with great feet. He is amorous

of the most voluptuous nymph, her of the twin disturbing hills.

He has remembered his ritual day, the noontide rites of the wine,

the flung flowers, and the shaken seed. He is approaching, he

will make himself known in the form of a . . .

--Bull is worth

more than man in the sum of things.

The Perfessor lit a cigar and leaned

on the fence, looking over at the white bull with a happy expression.

--Where's this heifer? the Senator

said. Let's have some action around here.

--The Greeks, the Perfessor went

on, addressing his remarks to Mr. Shawnessy, were right to make

a god of bull. Christianity debased God by making him a grieving

and gibbeted Jesus. Fact is, man may well envy bull. Bull is

pure feeling, has no silly moral anxiety, exists entirely for

the propulsion of life.

--Bull doesn't know love, Mr. Shawnessy

said. Look at him. He's just a phallus with a prodigious engine

attached.

--Love? the Perfessor said. What

is love? Why, John, your bull is your perfect lover. His sexual

frenzy is much stronger than man's. Man's a popgun to him.

--Love is moral, Mr. Shawnessy

said. Passion's a form of discrimination. From among a thousand

doors, it chooses one. There's no great love without great conscience.

But your bull's no picker and chooser. To him, one cow's as good

as another. Jupiter erectus conscientiam non habet.

--Let's have some action around

here, jocundly bellowed the Senator. Where's this heifer?

pp. 589-90

ONLY ONE LADY PRESENT

The Raintree County Stockbreeders Association today held a meeting at which the Hon. Garwood B. Jones was the guest of honor, sharing the limelight with . . .

A great white

bull, eight feet tall, walked on his hindlegs like a man, stabbed

the air with blind hooves. Guttural shouts shook the fence. The

Senator's cigar fell from his mouth. The heifer staggered....

Squealing delicately, Mrs. Passifee

upset with a motion of her arm the little table next to the sofa,

and looking sideways watched the stone jug and two tumblers scatter

on the floor.

--It's all right, she whispered.

Nothing's broke but one of the glasses.

Preacher Jarvey made no reply.

His brows were bent into a majestic frown.

Listen, I am the god. I was waiting

in a cavern of this island. From among all the vestals, I select

you. Do you run from me, little frightened sacrifice? Do you

hear the thundering hooves of the god behind you? Do you feel

the hot breath of the god on your slight shoulders? Listen, I

hear your cries, your virginal complainings. Our island is small,

and you cannot escape me. You shall be made to feel the power

of the...

--Lord help me! Mrs. Passifee sighed

resignedly. I'm a poor weak woman.

The Preacher said nothing, but

closed his eyes.

Who can love god as god would be

loved? Only the most beautiful of mortals. Only the most tender

and compliant. But who can love god as god would be loved?

--Sakes alive! Mrs. Passifee said,

gasping for breath. You're a strong man, Brother Jarvey.

O, I remember how they reared the

great stone shaft in the sacred isle. I remember the sweet assault

of all the unwearied dancers. Pull down over the column garland

after garland of flowers. Wreathe and ring it with tightening

vines. Dash wine and the petals of roses against it. Dash it

with waves of the warm sea.

Even the god shall enjoy the pastime

of mortals. Great is his rage, he is tall in his amorous fury,

goodly Dionysus. Bring grapes, he tramples them, raking the ground

with his horns. Let him forget that he is god, goodly Dionysus.

Let him be only desire on the peak of fulfillment. Let him be

only feeling and fury in doing . . .

--The act of love, said the Perfessor, leaning on the fence and watching intently, bottle in hand, is an extraordinary thing. At such times we are like runners passing a torch. We pant and fall exhausted that the race may go on.

pp. 593-4

--God, said

Mr. Shawnessy, is the object of all quests, and love is the desire

with which we seek Him.

--I have been winding through the

labyrinth, lo! these many years, the Perfessor said, as they

came out on the National Road, and my clue has led me to the

Answer. God is a Minotaur, who demands the blood sacrifice from

us all.

Mr. Shawnessy saw his two oldest

children, Wesley and Eva, standing with Libby Passifee and Johnny

Jacobs, peering into a front window of the Passifee home. As

he watched, they all turned and ran through the gate to the road.

He stopped, waiting for them. They looked startled and shy.

--Hello, children. Oughtn't you

to be at the school?

--We came home with Libby for a

book they were supposed to have for the rehearsal, Wesley said.

They went on rapidly toward town.

Mr. Shawnessy saw no book.

--The Answer, he said, is in us,

around us, everywhere. The Answer is every moment of ourselves.

The Answer is a single unpronounced and unpronounceable Word,

that could at one and the same time denote everything and connote

everything.

--Sometimes, John, the Perfessor

said, your reasons are better than reason.

pp. 869-70

CONTENDING at the intersection, the Nation

east and west and the County north and south, Esther Root Shawnessy

was passing in the early evening, coming from the Schoolhouse,

where she had stayed to help clean up after the Patriotic Program.

She was thinking now that she liked Waycross best of the towns

in Raintree County, perhaps because the National Road passed

cleanly here through the troubled earth of the County, crossing

the old boundaries, dissolving the old obligations.

Approaching the intersection, she

watched Pa drive by in his buggy beside the Reverend Lloyd G.

Jarvey. Pa saw her and nodded but said nothing as he and the

Preacher turned north toward the Revival Tent. She had heard

that there was to be a special meeting of some kind at the Tent

tonight, but she hadn't been invited.

The warning Pa had given her earlier

was in her mind. He had said that she would find out before the

day was over that her husband was fooling her. All day she had

vaguely wondered at the threat. Perhaps it meant no more than

that the voice of scandal, easily raised in small towns, had

accused some woman of being in love with Mr. Shawnessy.

If that was the case, Esther wasn't

disturbed. She had always known that other women loved her husband.

When she had been a little girl, the other girls had loved him,

though of course none so passionately as she. Now that she was

older and married to him, she still expected that other women

would be in love with him. It was impossible to know him without

being in love with him--or so it seemed to her. For that matter,

Mr. Shawnessy might love other women--as he loved and admired

Mrs. Evelina Brown. Whatever was virtuous, beautiful, and feminine,

he loved. But as for his being to any other woman what he was

to her, Esther considered the idea simply absurd. ...Mr. Shawnessy

could no more cease to be her husband, through any act of his

own, than her father could cease to be her father.

pp. 1005-9

HER NAME was being called in

the garden.

In the cool of the evening, when

a thin dew gathered on the grass and the air was still, and it

was summer at the end of a long day, and the light had been long

gone from the sky, and the crickets chirped, and the grass was

tingling cool on her bare feet, and there were dark corners of

a lawn, and the night bugs beat themselves to death on the window

panes, and darkness was full of distant and vague tumults, she

would almost remember. She would listen then for the voices deep

inside her, the voices from long ago that said,

--Eva! Eva!

They were calling for her and coming

to find her, and she was in the attitude of one listening in

beautiful and dark woodlands, and waiting for them to come.

This was a memory then of the very

first of the Evas, the dawn Eva. Sometimes in the afternoon,

when she had been sleeping and awoke to hear a sound of flies

buzzing at the window panes, she would almost remember that Eva.

It was the lost Eva, the one who had lived in a summer that had

no beginning nor any ending, beyond time and memory, beyond and

above all the books--most legendary and lost of Evas!

Now she was in the round room at

the top of the brick tower looking down at the other children

playing. It was Maribell's playroom, and here Eva could imagine

that she was a princess in a lonely tower looking down on strange

tumults in a legendary world.

Leaning on the window ledge, secure

in her tower, she was remembering the pantomimic scenes that

had flickered across the stage of the garden a half-hour before,

just after she had first come up to the tower.

It had begun with the torches that

had flared up suddenly in the town and moved toward Mrs. Brown's.

There had been a burst of song, and the torchbearers had stopped

in front of the flungback iron gates of Mrs. Brown's yard.

At first, Eva had wanted to run

down, but she could see so well from her place that she remained

listening and watching, fearful that it might all be over before

she entered the scene.

The leader of the marchers had

been the Reverend Lloyd G. Jarvey. There were about fifty men

and women in a column, most of whom appeared to be strangers,

while on the fringes of the torchbearers little knots of townspeople

hovered.

Preacher Jarvey had walked straight

up to the open gates and had stood between them. Eva had seen

the torchlight reflected on his glasses. The Preacher had shouted

something in his deep voice, and Eva's father had walked down

to the gate. The Preacher had shaken his finger in her father's

face, and as he did so, there was a low grumbling among the men

in the crowd. Three or four rough-looking strangers had come

up pushing a tub of steaming stuff on a wheelbarrow. The torches

had burned smokily, flaring and sputtering.

Then Eva realized that her father

was in danger, and she had been on the point again of turning

and running downstairs.

But just then Professor Stiles

had walked briskly down to the gate, his sharp, high voice cutting

the air like a whip above the crowd. His long, thin arm swinging

a cane had extended, pointing at the Preacher, and Eva had caught

the words,

--... happen to be ... wellknown

doctor of theology ... great city of New York ... think you are

anyway, you ... promise you ... every scalawag in this party

... disturbing the peace, trespassing on private ... person of

an innocent ...

The Preacher had shouted something

back, and Eva's father had said something, and the Preacher had

pointed at Mrs. Brown and at Eva's father. Mrs. Brown had shaken

her head violently, and Eva's father had squared his shoulders

and said some very crisp words that Eva couldn't make out and

had opened his arms as if in appeal to the whole crowd of watchers

beyond the gate. The Preacher had turned and made a motion of

calling someone from the crowd, and a woman who looked like Libby

Passifee's mother had stood forth and come up to the gate and

talked in a shrill voice.

Once again, Eva had been on the

point of running down to the yard, when another amazing thing

happened. Her brother Wesley was pulling Professor Stiles' arm

and pointing to the Preacher and then to the Widow Passifee.

Professor Stiles had raised his cane and, waving it, had shouted

in a piercing voice,

--Silence! Silence!

The crowd had quieted down a little,

and Wesley had said something else, still pointing at the Widow

Passifee and the Preacher. Then Johnny Jacobs had stepped up

and vigorously nodded his head and pointed his finger at the

Widow and the Preacher. The Preacher began to bellow over and

over

--It's a lie! It's a lie!

And Wesley had pulled Libby Passifee

out of the crowd of children and had made her admit something.

Professor Stiles had shaken violently,

and the crowd had began to snicker. The Widow Passifee was shaking

her finger at her daughter Libby and threatening her some way.

Johnny Jacobs had said--in a very loud voice,

--He didn't even have his glasses

on!

Professor Stiles had shaken soundlessly

again, and the crowd had snickered again.

And the whole crowd had begun to

shake their heads and laugh and draw away from the Preacher.

The Widow Passifee had shrieked something and walked away very

fast toward her house. The Preacher had remained in the entrance

to the yard, peering from side to side.

Just then, Professor Stiles, who

had been pacing briskly back and forth like a trial lawyer in

a crowded courtroom, walked decisively down to the gate and began

to harangue the crowd. Eva caught the words,

--...duped and led astray ... exciting

you to frenzies ... final act of madness ... guilty of committing

himself!

At this point, the Preacher had

flung down his torch and, raising both arms, had bellowed like

a bull. He had made a lunge at Mrs. Brown, but Professor Stiles

had planted himself in the way and, pointing his malacca cane

before him like a fencer, with a single deft motion flipped the

Preacher's spectacles into the night. Thereupon several townspeople

had thrown themselves upon the Preacher, and the Preacher had

butted, lunged, and struck blindly in the darkness. Professor

Stiles, remaining well out of danger, had occasionally rapped

the Preacher sharply on the head with his cane or jabbed him

in the seat of the trousers. So doing, he had appeared to whip

the whole struggling mass through the gates, which he promptly

slammed to. The Preacher had turned and reared at his assailants

and in spite of blows had broken through and struck fists and

head against the iron gates before he realized that they were

shut. Then abruptly he had turned and run down the road into

Waycross, with short steps, hands open before him like a man

half-blind and beset by pestering sprites.

Several people had come up from

the road and said something to Eva's father, and some women had

come and talked with Mrs. Brown, who kept putting her hands against

her cheeks and shaking her head.

Eva's mother had stayed beside

her husband the whole time, but she too now went over and said

something to Mrs. Brown. Everyone seemed to be very sorry about

something, except Professor Stiles, who seemed very happy about

something.

Suddenly realizing that the excitement

was over, Eva had gone tearing downstairs. She had hunted Wesley

and had found out what had happened. It seemed that the Preacher

had gone crazy and had come down to accuse their father of doing

something bad and being an atheist. Their Grandfather Root's

name had been mentioned, and he was mixed up in it some way.

Then Wesley had told what the children had seen in the morning,

and that had got the Preacher in hot water, and everyone had

laughed at him. Wesley was a hero, and so was Johnny Jacobs.

--Just go back to your playing,

children, Eva's father had said. In a little while, we'll have

those fireworks.

Then the people had gone on back

to the town, and the children had started up the game again,

and Eva's father and Professor Stiles had gone back to the porch

again.

Eva hadn't felt like playing any

longer. Instead, she had wandered away again and had come back

to the tower and had remained at the window looking out again,

wondering if she was missed.

Even now the night was restless

with sounds--the last explosions of firecrackers, the last buggies

leaving Waycross to go home, the tagends of the Revival crowd

breaking up. The night was full of terror and mystery. Always,

she had known that the earth of Raintree County was full of dragons

breathing fire. She had known too that the dark image of her

grandfather would haunt her life. She hadn't quite realized how

serious the danger had been until it was over.

As long as there were little children

and faithful women around, her father would be safe, and so long

as her father was safe, she would be safe. The voices and the

lanterns had advanced even to the gate and had almost broken

in, and then they had been driven back; the flickering cane of

Professor Stiles had chased them down the road.

Now all was well, and the night

was kept from the garden by colored lanterns and by the shrill

excitement of the children at their games. The evil ones had

been defeated by their own evil.

pp. 1055-6

But in the next

moment, the Perfessor, acting as usual, shook with amusement.

The sweet, forlorn look came back into his eyes, and he laid

the Atlas on Mr. Shawnessy's lap.

--There you are, he said. Keep

it yourself, boy. It's your own Raintree County and no one else's.

Forever the little straight roads shall run to lost horizons;

and in the niche reserved for justice, the image of young love

and soul-discovery forever shall be poised. It shall be there

for you alone, in your unique copy of the universe.

A low thunder of wheels was swelling

from the east. A red eye glared in the dark, grew astonishingly

big and close. The agent swung his lantern athwart the rails,

and the train rolled heavily to a stop in Waycross Station. Instantly,

a figure, resembling the Reverend Lloyd G. Jarvey, appeared from

the darkness and climbed into one of the rear coaches.

--O, o! croaked the Perfessor,

who hadn't missed the movement. The Lord God Jehovah and I are

getting out together.

| The Novel | Essays | Other Writings | RL Jr. Writer's Award | Complete Contents | Book Orders |

| The Biography | Photos / Postcards | RC Source & Facsimiles | Suicide & Prevention | Movie & Score |