|

"THE SONG OF 'RAINTREE COUNTY'"

The Great (Almost) American Novel Becomes The Great American Film Score

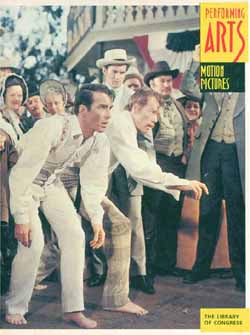

Performing Arts Motion Pictures,

Iris Newsom, Editor.

The Library of Congress,

Washington, DC, 1998

Ross Care's RAINTREE COUNTY Library of Congress article OnLine:

Author's

Introduction: Many hours of my child-and-young adulthood

were spent in the movie theaters of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

This combined with a burgeoning interest in composition and music

in general and film music in particular led to my early literary

efforts to write seriously about the motion picture music of

the late (and declining) Hollywood studio era, the last days

of which I was then experiencing. Like many young Americans of

this period I had also been fascinated with the animated films

of Walt Disney that, after a brief decline in the 1940s, went

into a major renaissance during the formative decade of the 1950s.

Indeed with the various technical innovations (and gimmicks)

of the '50s 3-D, Cinerama, CinemaScope, and Camera 65 -

film music in general also peaked at this time, moving into what

I consider to be its last great classic period.

Part of

this Golden Twilight of the Hollywood studio system was MGM's

film version of Ross Lockridge, Jr.'s epic novel, RAINTREE COUNTY.

Composer John Green's musical score for this film was (and is)

my favorite film soundtrack LP of the period. But the fact that

I was practically the only writer of the period to deal seriously

with the unique music for the classic animation of the Disney

studio helped me first break in print with articles on the scores

and (still generally little-known) composers for the Disney oeuvre

from 1928 through the '50s and early '60s.

I wrote

an extensive piece on Disney composers, "Symphonists for

the Sillys," for Mike Barrier's legendary animation magazine,

Funny World. This came to the attention of Jon Newsom,

then head of the Music Division of the Library of Congress in

Washington, DC, and also a force in the early documentation of

classic film music during this time. Also a pioneering serious

admirer of Disney and animation music in general, Jon invited

me down to the Library at that time I was living in Lancaster,

PA. and indicated that if there was anything of interest

(!!!!) among the Music Division's vast holdings that I'd care

to write about the Library would be interested in publishing

it. I was of course fascinated with the Library's major collection

of original Hollywood scores that had been sent there for copyright

purposes during the last several decades.

Jon's wife,

Iris Newsom, of the Library's Publishing Division, was launching

a new series of deluxe hardback books at this time, what were

originally called the Performing Arts Annuals, each to

deal with the holdings of the Library's various divisions, Music,

Motion Pictures, and so on. My first article in Performing

Arts Annual 1986, was autobiographical, "Memoirs of

a Movie Childhood," and deals with growing up with movies

in the theaters of Harrisburg, and the American movie going experience

of the period in general. It was illustrated with film stills

and graphics from the Library's Motion Picture division, these

augmented with historic theater photos from the Pennsylvania

State Archives (including a photo of Loew's Regent Theater in

downtown Harrisburg where, during my high school years, I first

saw RAINTREE COUNTY in 1957). After this I contributed a variety

of articles to the PA series, including major articles on Cole

Porter and Alex North, these peaking in 1998 with two articles

for Performing Arts Motion Pictures in 1998.

For this

volume I contributed two articles: "Twilight's Last Gleaming,"

an overview of Hollywood music from 1950 to 1965, and the essay

on RAINTREE COUNTY that follows. The RAINTREE article deals with

both the original novel and its film version from my personal

relationship with both during the late '50s, but it also focuses

on John Green's great score, which is by now considered one of

the strongest elements of the film and one of the great Hollywood

scores of all time.

It should

also be noted that this essay only deals in depth with the first

third of this very major score. But in late 2006, and now living

in California, I was approached by Film Score Monthly

in Los Angeles to write the liner notes for their forthcoming

two-CD restoration of the complete Green/MGM score. This was

released to much popular acclaim in early 2007, at the time three

RAINTREE threads on FSM's website message boards collectively

garnering thousands of hits. For this CD release, which followed

the original (and incomplete) RCA Victor albums which were in

turn re-issued in several formats, I was able to discuss the

entire score, plus half a disc of rare bonus material. I should

also emphasize that I wrote the FSM notes "from scratch,"

i.e., they are not a re-write of the following essay and

anyone with an interest in the complete RAINTREE COUNTY score

is strongly urged to seek out the Film Score Monthly/Turner Classic

Movie Music CD restoration. (FSM

two-disc set, Vol. 9, No. 19).

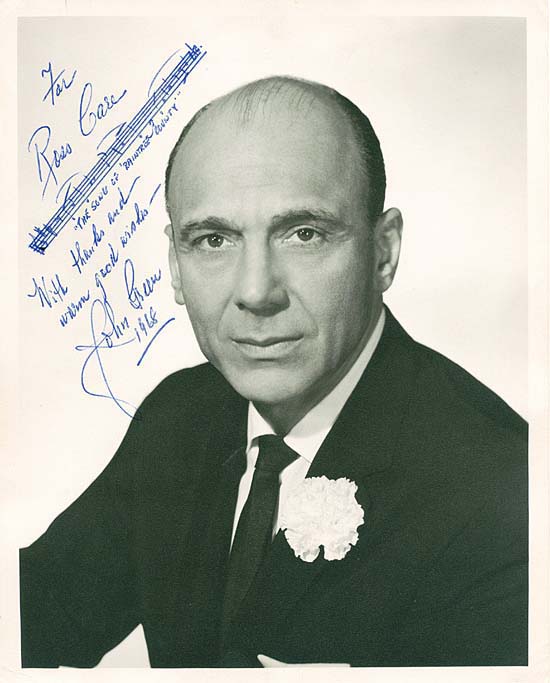

After graduating

from college I was still listening to RAINTREE COUNTY and was

inspired to write a letter to composer John Green. The following

essay also includes excerpts from Green's response, here included

in the article for the first time, along with the personally

autographed photograph he enclosed. These were sent from London

where he was working as musical director for the film version

of OLIVER! That his score and composing for films in general

was, at this time (1968) still essentially unrecognized, indeed

ignored, is indicated by Green's comment: "Your references

to the aesthetic reward or lack of same in connection with the

writing of film music triggers so large a topic as to rule out

discussion in a letter of this kind."

I can only

hope that somehow John Green and the other once-obscure composers

of this era are now somehow aware of the recognition and love

their then-unsung work has so avidly - even obsessively - inspired

and achieved over the past few decades.

And I'm

so grateful I was able to express my admiration and respect for

Green's own work to him when I did.

Ross Care, Ventura, California, June, 2007

Raintree County: The Period, The Novel

In the 1950s, when Hollywood optioned

seemingly everyone on the American literary scene for a movie

"adaptation", from Herman Melville, William Faulkner,

and Jack Kerouac to Erskine Caldwell, John O'Hara, and Grace

Metalious, it was often the era's unsung film composers who in

fact most vividly captured the American essence of these writers'

works in the often questionable film versions derived from them.

Indeed certain composers, such as Alex North and Elmer Bernstein,

became singularly noted for their ability to lend emotional life

to such grandiose attempts at bringing the printed page "to

life" onscreen.

North, of

course, began an auspicious career with his haunting music for

Tennessee Williams' Broadway play, "A Streetcar Named Desire,"

going on to evoke such varied but quintessentially American authors

as Faulkner: (The Long Hot Summer, The Sound and the Fury), Edward

Albee (Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?), and James Leo Herlihy

(All Fall Down). Bernstein's career moved into high gear with

his celebrated ` score for the film of Nelson Algren's contemporary

novel about drug addiction, The Man With The Golden Arm, and

continued to sympathetically enhance such diverse adaptations

as Algren's Walk On The Wild Side, Erskine Caldwell's God's Little

Acre, James Michener's Hawaii, and the best Tennessee Williams

film after Streetcar, Summer and Smoke. Very appropriately, Martin

Scorsese chose Bernstein to score his recent film of Edith Wharton's

The Age of Innocence.

Whatever

its other positive and/or dubious side-effects, going to the

movies in the 1950s provided a crash course introduction to both

American and world literature (including Shakespeare for whose

Julius Caesar MGM supplied Marlon Brando, Deborah Kerr, and a

Miklos Rozsa score!) Inexpensive paperback "movie tie-ins"

in Signet, Perma Book, and Bantam editions completed one's education:

along with many other works, you could purchase a play by Tennessee

Williams, complete with original cast and credits and a four-page

spread of movie stills, for thirty-five cents at your friendly

local drugstore or news shop. (When John O'Hara's mammoth "From

The Terrace" appeared at a whopping ninety-five cents a

copy it was considered an economic, as well as a literary scandal.)

In February

1957 a fifty-cent Dell paperback with a distinctive watercolor

cover of Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor in an intense

and obviously troubled embrace hit the stands: "Raintree

County" by Ross Lockridge, Jr. Above the title was the simple

claim "A great American novel", a remarkably restrained

avowal given the usually excessive and often lurid hype with

which most paperbacks (and films) of the day were promoted. While

a relatively modest addendum printed at the bottom of the cover

informed the reader that "Raintree County" was "now

a great Metro-Goldwyn Mayer production", aficionados of

film and literature (often one and the same in those culturally

rich times) already well knew it was an MGM movie, thanks to

breathless movie magazine accounts of Montgomery Clift's well-publicized

re-casting opposite Elizabeth Taylor (they had played together

in the depressing but popular A Place in the Sun in 1951) and

with whom, wags insisted, he shared an intense (if then puzzlingly

platonic) relationship. "Raintree's" pre-release notoriety

was further enflamed by the handsome Clift's disfiguring car

crash in the middle of the expensive production. Just how "great"

the film was, however, remained to be seen.

In small

print under the title's distinctive type font (only slightly

varied from the original hardback edition) was a single word:

"abridged". Whoa! The paperback edition clocked in

at 512 pages; for the prospective reader the inevitable question

was, how long might the unexpurgated version be? After at last

seeing the film (a very mixed but still strangely compelling

bag) further investigation led me to my local library and the

book's original full-length 1948 version, clocking in at 1060

pages and now disappointingly sheathed in the neutral (and very

uncinematic) binding of most library editions of the day, at

least for those books which managed to survive beyond their initial

best (or non-) selling print-runs. It was nearly a decade since

"Raintree" had been published, when I first found the

complete edition still available in the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

public library. (The generic library binding might also have

been a result of the novel's distinctive original dust-jacket

painting: an anonymous hand seen grasping what appears to be

either a canvas or map of an Arcadian landscape, the contours

of which form the graphic outlines of a female nude, a recurring

image in Lockridge's poetic and often highly erotic prose. An

alternative "Book-of-the-Month Club" edition featured

a somewhat less controversial dust-jacket illustration: Adam

and Eve clad in prim 19th-century garb, and receiving a golden

apple from an obliging serpent).

I first

experienced Raintree County, the movie, the book, and

its amazing musical score, at a formative period in my life,

my first years of high school which also spanned both the last

days of one of my favorite theaters, Loew's Regent in downtown

Harrisburg, its ultimate demise a precursor to the 1950s trust-busting

binge which spelled "The End" for MGM's chain of theaters,

and the last gasp of the Hollywood studio system in general,

of which "Raintree" was a key manifestation. I was

also flexing my wings as a composer and, thanks mostly to MGM

and Disney, and to having loved movies since the dawn of consciousness,

soon became instinctively and avidly aware of the era's vivid

film music.

Raintree

was one of the first films to really catalyze this life-long

fascination with music and image. As a budding orchestrator,

I was particularly struck by "Raintree's" basically

conventional yet inventive orchestration: for example, its simple

but distinctive use of a tambourine in the "Footrace"

and "July Picnic" sequences, and even more notably,

the wordless female chorus and mysterious shimmer of bell-like

sounds woven into the orchestra, which (belying the mundanely

literal visualization in the film itself) actually turned "Johnny's

Search For The Raintree" (as the soundtrack album identified

the cue) into the mystical experience adumbrated on the back

of the paperback edition: "The legend of the Raintree is

the age-old tale of man's quest for the unattainable. In every

time and every language poets have sung of it - the Tree of Life

in the Garden of Eden... Apollo's tree bearing golden apples

in the Garden of the Hesperides....mysteriously transplanted

to the heart of frontier America." Pretty heady stuff for

a 16-year old, but Johnny Green's ecstatic, pantheistic score,

a sensual and highly empathetic evocation of Ross Lockridge,

Jr.'s unique, multi-faceted novel, made it all palpably real

and possible, and in a manner much more haunting and visceral

than the film itself.

In an era

when stars like Clift and Taylor were the profusely publicized

gods and goddesses of creation by a relatively restrained (by

today's

standards) media, I had no idea who either composer Johnny Green,

or author Ross Lockridge, Jr., were (though I was struck by the

fact that I had finally found a namesake somewhere in the arts.)

What I did know was that something about "Raintree"

struck a chord deep within me, in no small measure because of

its evocative musical score, making the film itself an unforgettable

experience which I longed to recapture. So, on my first visit

to the legendary Sam Goody record store in New York, I found

myself agonizing over whether I should buy the two-record RCA

Victor album of the "Raintree" score, an unprecedented

and expensive (for a high-school student) item at the time, or

settle for the single-disc "highlights" album so as

to also afford the first relatively complete soundtrack of "Snow

White" which had also just been released as part of the

new Disneyland Records series of WDL-4000 original soundtracks.

Such were the naive consumer quandaries of the popular culture

addict of the late 1950s!

I never

regretted settling for the "Raintree" highlights album,

and "Snow White," but when I finally acquired the double

"Raintree" album some years later (at a much more expensive

price as a highly sought-after out-of-print collector's item),

I was thrilled anew by a score which in the meantime had become

one of my (and many people's) most durable favorites, a thrill

experienced again on listening to recent CD re-issues. (In 1972

the July issue of "High Fidelity" was devoted to film

music and listed the then-current going-price for the two-record

"Raintree" set at $150.00, while also imortalizing

the tantelizing anecdote about the legendary "Raintree"

cut-out double albums which had allegedly very briefly surfaced

at Goody's bargain outlet in NYC!)

I've never

really stopped listening to Green's score, and when I guested

on my local PBS station's "Desert Island Discs" radio

program a few years ago, I had no qualms about including a track

from "Raintree" - the beautiful and self-contained

"July Picnic" cue which had so stuck me on my original

viewing of the film - as a sample of one of the eight discs with

which I would select to be shipwrecked. And of course Green's

score, and the film which occasioned it, led me to the original

novel which the music so vividly evoked, and to the curious,

quintessentially American and conflicted life of the novel's

author, Ross Lockridge, Jr.

"Raintree

County," the novel, has maintained its reputation and place

in American letters strongly enough to have inspired two biographies

of its author, "Ross and Tom" by John Leggett, and

Larry Lockridge's "Shade of the Raintree: The Life and Death

of Ross Lockridge, Jr." (though both the dust-jacket and

title page of the latter book make sure to identify Lockridge

as the "Author of 'Raintree County'", in deference

to contemporary readers presumed unawareness). Larry Lockridge's

fascinating book addresses everything that anyone who has ever

gotten though his father's intimidating yet fascinating tome

might wish to know, providing many of the details of family history

and background which Ross wove into the book, as well as the

saga of its publication and exploitation.

But the

blurb on the back of the original dust-jacket sums up the "Raintree"

saga in a nutshell: "In April of 1946, Ross Lockridge, Jr.,

carried 'Raintree County' to the office of the Houghton Mifflin

company in a suitcase. The manuscript, weighing twenty pounds,

was piled on a table in an antechamber, where the author and

editor sat peering at each other over and around this Matterhorn

of literature. In a few weeks the manuscript was accepted and

a contract signed. Still to come were the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Novel Award and other successes for the Indiana writer's first

novel. The contract, however, was the first tangible reward of

a determination made by Lockridge at the age of seven to become

a writer." The PR for the original edition, superficially

a classic American literary success story, could not foresee

the unhappy conclusion of the "Raintree" saga, nor

could anyone reading this terse literary success story have envisioned

the tragic real-life denouement of the author: in March of 1948,

before any production work on the film had begun, Lockridge shut

himself in his family garage in Bloomington and committed suicide.

The somewhat

rocky cinematic history of "Raintree County" was fairly

assured by its having won the lucrative MGM Novel Award. Larry

Lockridge describes the competition as follows: "First held

in 1944 in a highly publicized campaign to corral valuable literary

properties, the contest would be increasing the award in 1947

to $150,00 for the author, $25,000 for the publisher, with several

escalator clauses that would bring the total to $275,000 for

the author. The sum $150,000, the equivalent of $1,050,000 in

1993 currency - with escalators, close to $2 million - was the

world's largest literary prize.

"My

father was unimpressed. The rules guaranteed no role to the author

in scripting or production, and he was an author who wished to

control his novel's fate to its extremities. He noticed that

previously winning novels were 'flashy, vulgarly constructed

novels with an obvious eye on the movies,' and no distinguished

films had yet resulted. He wished to script any film adaptation

himself." 1 The eventual MGM ad campaigns

for the film touted the film as being based on "the prize-winning

panoramic novel" while neglecting to mention they had bestowed

the prize themselves! (The grandiose double-page movie magazine

ads also hyped the film, shot in the new big-screen process,

"MGM Camera 65," as being "In the great tradition

of Civil War Romance," a tacit reference to "Gone With

The Wind," which "Raintree" recalled only in its

period setting. The author's name appeared in the last line of

the copy, in type considerably smaller than the "Print by

Techicolor" credit).

Like its

predecessor and most covert influence, James Joyce's "Ulysses,"

"Raintree County" is the story of one day, "A

Great Day for Raintree County, July 4, 1892," and like "Ulysses"

that day is described through a complex filigree of flashbacks

and stream-of-consciousness monologues and narratives. No less

than three chronologies - one for the events of the day itself,

one listing the chronological order of the incidents described

in the flashbacks, and one for the actual historical events that

bear on the plot - are included to "assist the reader in

understanding the structure of the novel." 2

Perhaps only Alain Resnais or some such auteur of the European

New Wave (or now a television mini-series), could possibly do

justice to the original Lockridge novel, a book "written

by a modern for moderns," as the dust jacket also announced.

In 1950s Hollywood, with its emphasis on linear narrative and

near hysterical romantic emotionalism, "Raintree County"

was (next to the then utterly unfilmable "Ulysses")

a screenwriter's worst nightmare come true.

Composing The Music of RAINTREE COUNTY

Composer Johnny Green (who, after a short period at the studio

in the early 1940s, took over the position of general music director

for MGM in 1949, and who originally studied economics at Harvard

before gravitating to a career in music) was, besides being a

consummate conductor, music director, and composer/song-writer,

an articulate scholar and gentleman of the "old school"

whose expertise far exceeded the realm of music. His observations

on the problems involved in transcribing the original novel to

the screen are astute: "The novel from which the screenplay

was taken was by no means a straight line story. Though effective

and moving, it was diffuse and involved. Its emotional complexities,

its criss-crossing tensions and surges, its heterogeneous flashbacks

demanded of the reader the greatest possible concentration. One

found oneself time and again turning back to refresh memory and

re-establish contact. These problems had to be faced by Millard

Kaufman in constructing his screen play and by Edward Dmytryk

in interpreting the development of the story and the characters

on the screen." Green discreetly but frankly concluded:

"Despite their great skill, vestiges of the diffuseness

and involvement of the original came through on the screen to

some extent and presented serious problems to the composer."

3

Green

goes on to describe some of these musical/dramatic problems and

his potential solutions:

"My first decision had to do with general approach. The time: mid nineteenth-century. The place: a fictional and prosperous county in Indiana just preceding, during, and immediately following the Civil War. The atmosphere: the fantasy of the Legend of the Raintree (symbolizing Man's endless quest for the unattainable) superimposed, in not too clear-cut a fashion, on a most realistic and practical set of situations.

"What should be the style, what should be the context of the music? Would there be the inevitable juxtaposition of 'The Battle Hymn of the Republic' against 'Dixie'? Should the score be based on indigenous music of the period? Should the music have a 'modern sound' and, if so, to what extent? Should block color or melody be the predominant characteristic? I even considered the possibility of a totally source music score, meaning that all the music would come from a source within the action, either seen on the screen or implied.

"Almost immediately I ruled out source music in favor of a completely theatrical approach. Next, I vowed that there would be no 'Battle Hymn/Dixie' goings-on and that the thematic material would be original (to the degree that this is possible with me). I then determined that the score should be romantic in feeling, that it would be melodic and that it should have what we know as 'that modern western sound,' not 'Wagon Wheels' of course, but rather the pentatonic and, to some degree, polytriadic sound that, under the able aegis of certain composers too well-known to require mention, has become the trade mark of the open spaces in recent serious American music." 4

Probably the most striking aspect of the score as I've come

to know and study it over the years, is its timeless simplicity

and elusive style, the result of a dynamic fusion of most of

the techniques described above. Green's music does not have the

immediately recognizable style of North or Elmer Bernstein in

their peak period, yet neither does it sound like anyone's else.

And, despite of what Green himself notes about the influence

of serious American composers, he nonetheless manages to evoke

a vivid, haunting sense of Americana without resorting to the

Copland-isms he himself suggests in the above quote.

As a composer

Green also has the strong, concentrated melodic and harmonic

sense of a great songwriter, as witness his harmonically audacious

"Body and Soul" with its unprecedented modulations,

and the more straightforward but equally haunting "Easy

Come, Easy Go," which Green later integrated into the score

of "They Shoot Horses, Don't They?" (1969), unfortunately

his only other major score to equal "Raintree's" significance

(though his contribution therein is primarily as musical supervisor/arranger

for period standards which supplied a bitterly ironic counterpoint

to this frankly depressing account of 1930s dance marathons).

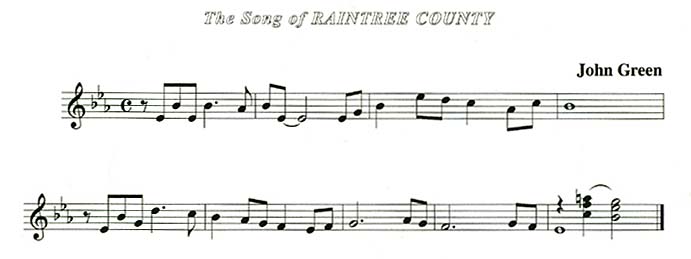

The "Raintree"

score takes its essential character from "The Song of Raintree

County," and is thus basically lyrical, or "melodic"

as Green also notes above (while also integrating aspects of

the "block color" approach he also cited). The song

is also a rare instance of a title tune satisfying both the artistic

and commercial demands of the medium and industry. Green spoke

frankly (and with the voice of one who, as head of the expensive

MGM music department, took such considerations in his stride)

about the decision to include an exploitable title song in the

context of a serious historical drama: ".... a practical

and perplexing problem... Should there be a song? The current

vogue in so-called title songs has become a bugaboo to all of

us who work in films. That it has been overworked to a fare-thee-well

there is no doubt. That a smash title song ranks high among the

top exploitation and promotion media that a movie can have is

also an established fact. That 'Raintree County' represented

a cost of over five and a half million dollars was already common

knowledge when I approached my job. Could I, in good composer's

conscious, accede to the pressure for a title song? I decided

that I could. Hence, 'The Song of Raintree County' with lyrics

by Paul Francis Webster." 5

|

Green

also decided to apply to the score as a whole a technique somewhat

eschewed in modern film scoring, the use of leit motifs. The

epic nature of the story itself, combined with its melodramatic,

near-operatic characterizations and incidents - a mad heroine

straight out of a Southern Gothic "Lucia"! - made such

a choice both practical and appropriate. "What to do about

the diffuseness, the multiple lines, the crisscrossing emotional

conflicts? Decision: straightforward leit motif. A theme for

every important character (or combination of characters), locales,

emotional element. Result: thirteen thematic entities with specific

story identifiability (there are additional transitional and

independent motifs, of course). Thus I hoped to provide certain

clarifying 'islands' or 'audio-reminders' that would help the

audience, if only subconsciously, to orient individual events

and character relationships to the whole." 6

One might also bear in mind that "Raintree"

was a product of the pre-video age when audiences were expected

and indeed required to digest a film in one viewing (or at most

only a few) during its relatively brief release (though, like

a few classic, i.e., especially expensive MGM offerings, "Raintree"

was briefly re-issued).

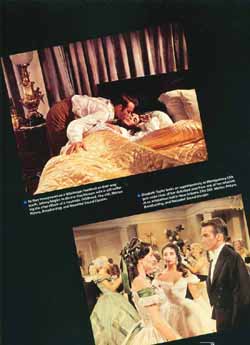

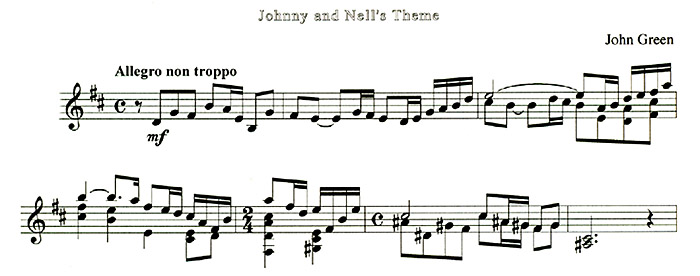

Both film

and score fall into three major sections, following the linear

plotline, which focuses primarily on the hero, John Shawnessy

(Montgomery Clift) and his two conflicting loves, that screen-writer

Kaufman extricated from Lockridge's complex and cross-dissolving

paean to 19th-century America. In the process (and probably of

necessity!) about two-thirds of the characters and incidents

in the book were discarded. The film's opening sequences describe

the hero's late youth and coming of age in a mystical pastoral

Indiana, and his naive relationship with his college sweetheart,

Nell Gaither (Eva Marie Saint). In the middle section the plot

thickens as he is tricked into marriage with a beautiful but

disturbed Southern belle, Susanna Drake, (Elizabeth Taylor) and

this section also tracks their atmospheric, indeed Gothic, interlude

in New Orleans and the pre-Civil War South of the girl's troubled

childhood. The third and final section brings on the war, and

the birth of John and Susanna's son, leading to Susanna's demented

flight south during the war, her temporary restoration but eventual

death prior to the happy and decidedly non-Lockridge Hollywood

ending as Johnny walks off into the sunset with his own true

love, Nell, under an imposing (if botanically incorrect) Raintree!

Important secondary characters maintained from the book include

Johnny's mentor and companion, the arch and Byronic "Perfessor"

Jerusalem Styles (Nigel Patrick); the brash but good-hearted

rural rake, Flash Perkins (Lee Marvin ), initially Johnny's opponent

in the July 4th foot race but later his Civil War buddy; and

Johnny's rival, the smarmy politician Garwood B. Jones (Rod Taylor).

Impossibly

managing to both tie together and ultimately galvanize a problematic

screenplay, Green's lyricism (embodied in his evocative sense

of orchestral color and skillful, dramatically astute contrapuntal

development) magically evokes the essence of Lockridge's complex,

overtly sensual and pantheistic novel to a far more sublime extent

than anything else in the pedestrian (if maddeningly charismatic)

film version. The visual iconography of Clift, Taylor, and Saint,

and the near-Hardyesque ambiance of the location shooting (Nell

sweeping through a lushly Arcadian landscape as Green's motif

for she and Johnny sweepingly sounds the Olympian promise that

their college graduation and Lockridge's book both celebrate

and lament; the eerie visit to Susanna's burned-out plantation,

with its brilliant musical equation of psychosis and racial hysteria)

sublimely capture the despairing glory to which Lockridge's valiant

book is a testament. And of course Green's score is absolutely

it, the most magical mystical element in a movie that unfortunately

eventually runs out of both steam and conviction over the course

of two-hour-plus running time. But despite these few (and not

inconsequential) positive elements, MGM/Hollywood star quality

at its best, and Green's superb score, the film is frankly a

travesty of the author's Joycean stream-of-consciousness narrative,

as how could it not be in an era when screenwriting rigidly adhered

to a strictly linear mode of plotting.

The Beginning of The End: The Studio System in the Late 1950s

Raintree County was among the last "big"

pictures produced in Hollywood with the considerable and heretofore

durable resources of the studio system, resources which were

already beginning to crumble during the 1950s. An 1954 article

on the MGM music department (where money once flowed like water)

commented: "Whether Johnny Green's financial training influenced

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to name him administrative head of their

music department, with its $2,000,000 annual budget, I do not

know, but the fact remains that a dollars-and-cents outlook carefully

governs his actions as head of this complex activity. With a

contract composing staff which includes Miklos Rozsa, Bronislau

Kaper, Andre Previn, Adolph Deutsch, George Stoll, Jeff Alexander,

Charles Wolcott, and Green himself, MGM seldom goes outside its

own walls for free-lance compositional talent. The current policy

of restriction to staff composers is influenced by the considerations

of economy, a major factor in all Hollywood operations today

in view of the uncertainties created by TV competition and the

unsettled problems of 3-D and stereophonic sound, etc."

7

As

general music director it was Green's responsibility not only

to assign the various composers their films, but also to oversee

the placement of music therein. In the mid-1950s MGM still maintained

more than one hundred persons in the music department as a whole,

including (besides composers) arrangers, conductors, copyists,

librarians, orchestra players, music coaches, and administrative

personnel. Green also cited the "decidedly controlled editorial

supervision" of the studio's music, noting that a kind of

musical "script" was prepared for all of the studio's

dramatic pictures. Running as long as ten to twelve single-spaced

typewritten pages, these scripts completely outlined the use

of music in each picture: its general character, whether it dominates

or is "under" the action, etc. (The music "script"

might be compared to a "story treatment" which sets

out similar parameters for a film's dramatic requirements). During

the period of Green's administrative duties at MGM, it was he

and his associates, including the producer and director, who

fashioned these musical outlines, usually watching the unscored

picture countless times, re-running sequences that were under

particular musical consideration. Ideas and comments were taken

down verbatim and roughed into the music script which was then

presented to the composer who, along with Green and his staff,

prepared a cue-sheet with exact timings for the musical episodes.

Once finalized, this cue-sheet, with its split-second timings,

was the final guide for composer and conductor. 8

Green's

final score for "Raintree County" is notated in five

bound volumes, the first of which represents a version of

the musical script described above. Besides detailed timing

charts for each musical cue, often with references to the actual

spoken dialogue in each sequence, volume I also includes Green's

personal notes and comments to the various arrangers (most taken

from his actual pencil score) who assisted on the film, and detailed

cue-by-cue lists of the instrumental and vocal ensembles required

for recording, as well as instructions as to when and how these

orchestral/vocal tracks were to be linked and superimposed on

one another, special effects (such as "reverb"), and

lyrics for both the Main Title and "Never Till Now,"

the song developed from the euphoric Johnny/Susanna love theme.

Concerning

his use of a staff of arrangers Green wrote: "An orchestrator

by profession, I compose my motion picture dramatic music in

detailed, seven line orchestral sketches. Why not, then, go the

rest of the way and work in full score? Because, even before

the panic sets in, there just isn't enough time under the scheduling

system that prevails. The small time spread between even the

most detailed sketches and the full score provides the differential

between 'making the date' and not making it. There is no orchestration

credit on 'Raintree County' because the overwhelmingly major

portion of the score was committed to paper in my own fully detailed,

seven line sketches. When, however, towards the end of the composition

period, my remaining time was suddenly cut in less than half,

a group of talented, good friends rallied round to make the impossible

recording date possible. After meticulous projection room discussion

and sessions at the piano with me, Alexander Courage, Sidney

Cutner, Robert Franklyn, Conrad Salinger, and Albert Sendrey

each adapted and arranged my detailed sketches for certain remaining

scenes." 9 Volume I of Green's final

bound set also includes some credits as to which arrangers worked

on which sequences, these becoming more detailed towards the

end of both picture and score. The supplementary arrangers were

generally assigned specific sections of the film: Sid Cutner

handling the Civil War sequences in at the beginning of Part

II of the film, Conrad Salinger contributing the end cues, and

so on; Albert Sendrey, and some others seem to have worked on

a variety of cues throughout.

The Score(s)

definitive edition

Green's final five-volume score for

"Raintree County" is dated September 13, 1957, and

is dedicated to his daughter, Bonnie. Volume I is divided into

five sections, with sections II through V listing the actual

cues as they finally appear in score form in volumes II through

V. The score volumes are also arranged by reels: volume II/reels

1-6, etc. Cues are listed as they are heard in the film, and

also numbered G1, G2, etc., G referring to the sequence of the

pieces in Green's bound volumes. Exact timing data and instrumentation

for each cue are also included, and some (but not all) are dated.

These bound volumes are no doubt the "detailed, seven line

orchestral sketches" of which Green spoke in his liner notes,

and are indeed thoroughly notated, down to such minute technical

details as Green's notations for pedal changes in the harp part.

While Green's

original volumes are now at Harvard, the Library of Congress

in Washington also has photocopies of the original studio piano

conductor's score of the "Music Score of Phonograph album

'Raintree County'. Received on Dec. 11, 1957, this is the copy

sent to the Library by MGM for copyrighting purposes. The phonograph

album score, dated 6-25-57 by Loew's Incorporated, is in the

beautifully executed style of all the MGM scores of the period,

a key example of the meticulous work of the studio era's music

copying departments, while Green's volumes are done mostly in

free-hand pencil, clear and also quite meticulous, but not always

easy for the non-professional eye to decipher. An album of piano

themes, "The Music of RAINTREE COUNTY" (Robbins Music

Corp., New York, NY, 1957, $1.25), was also published at the

time of the film's release, and a copy (dated Nov. 19, 1957)

may also be found in the Music Division.

In the following

score discussion reference will be made to both the Green and

Phonograph Album scores, as well as to the written data and notes

contained in Green's volume I. Space considerations limit my

in-depth investigation of the score to cues from the opening

Indiana sequences (admittedly, for me, the most lyrical and atmospheric

sections of both film and score).

Section

one of Green's Volume I lists the film's major credits, and notes

that its world premiere was in Louisville, Kentucky on October

2, 1957. The composition period of the score is cited as November

1956-May 1957. The notes in section one pertain mainly to the

film's road-show engagement "Overture," but also include

Paul Francis Webster's first draft of his lyrics for "The

Song of Raintree County," dated April 10, 1957:

The way to Raintree County

Can't be found on a map or a chart.

Like me you'll find that Raintree's a state of the mind

or a dream

in your heart.Long ago one day

with the buds of early May

up you came like a flame from the South!

And I looked into (laughing eyes so bright and blue)

Eyes of periwinkle blue

and I knew;

then I knew - -I'd love you in Raintree County

and I'd learn what we all seek to know

We shared a golden dream when we found our true love

In Raintree long ago.For the brave who dare

there's a Raintree everywhere,

We who dreamed found it so long ago.

Webster's words are basically the same as those used in the

final version of the song; the main concepts are all there and

in need only of a few instances of fine-tuning. Green commented

that his challenge "...was to write a melody, with a certain

folk flavor, which would serve well as the thematic representation

of Raintree County itself, of a locale and its people, have popular

appeal as a song and yet dovetail with the color and style of

the total score," while Webster's was "...to use the

words 'Raintree County' with the title, to create a lyric that

would be comprehensible in today's incomprehensible song market,

to maintain some definite relationship between the words of the

song and at least the feeling , if not the story of the picture,

to be commercial and yet be literate enough to 'belong' in the

company of the rest of the elements of the film." 10

Webster,

who created effective lyrics for a variety of title songs from

the period, managed to tastefully meet the considerable demands

cited by Green. The main revision in the original lyrics quoted

above occurs in the first two lines, the lyricist opting to insert

a terse reference to the legend of the Raintree which suffuses

both book and film: "They say in Raintree County There's

a tree bright with blossoms of gold," then just slightly

varying the next two lines: "but you will find the Raintree's

a state of the mind, or a dream to enfold." The song as

a whole is compact, and the expected second A section (of the

usually strict AABA form of most pop songs of the period) never

happens; instead, Green and Webster move directly to the B (or

bridge) section with its reference to the Elizabeth Taylor character,

the "flame from the south." The final A section manages

to merge both the obligatory reference to "love," requisite

in any song of the period ("I'd love you in Raintree County....")

and finally the informing concept that Green refers to as "the

essence of the picture" and which serves as a kind of coda,

"..... For the brave who dare there's a Raintree everywhere,

we who dreamed found it so, long ago," a phrase which even

manages to suggest the original (and unpunctuated) closing lines

of Lockridge's book: "....of some young hero and endlessly

courageous dreamer"

Nat King

Cole (a rather curious choice for a film the heroine of which

is driven mad by, among other things, her paranoia over having

"nigra blood") performs the song as the film's Main

Title. Due to contractual restrictions Cole's version is not

included on the RCA soundtracks, but he did record "The

Song of Raintree County" as a Capitol single and on an LP

album of movie songs;11

while the single did not prove a major hit, the song itself

was included on many of the then-popular movie theme "mood"

albums of the day. Both scores include Cole's vocal line and

orchestral accompaniment, though only Green's includes the two

additional brief cues, "The Lion" (for the MGM logo),

and a transition into the song referred to as "Nat King

Cole Capitol Intro" which leads directly into the "Main

Title Nat "King" Cole version". A cue for the

12-voice male choral back-up to the Cole solo is included in

the Green score, but no copy of the mixed choral version arrangement

used on the record album is to be found in either score. A complete

version of the title song, and "Never Til Now," the

song developed from the Johnny/Susanna love theme (but not sung

in the film), are both included in the piano album as well.

The melody

of "The Song of Raintree County," a folk-like diatonic

theme in which the repeated perfect 5th intervals of the opening

phrases build to a poignant suspension effect on the word "find",

permeates the first third of the score, weaving into and out

of the cues and various other motifs in a manner richly suggestive

of the original novel's stream of consciousness style. No matter

how much new material is introduced in the score's opening cues,

each element seems to marvelously gravitate to a duly transformed

reprise of the title theme, thereby reinforcing the hyper-lyrical

"Raintree" motive (and its charged symbolic mythos)

in the minds and hearts of the audience.

Reel 1, Part 1: "Overture" - "Nell and Johnny's

Graduation Gifts"

Both scores open with the road show "Overture",

"adapted and arranged in part by Albert Sendrey from themes

by Johnny Green, ASCAP." The most complete version is found

in the record album score, while Green's copy omits the Susanna/Johnny

love theme which forms the middle section of the album "Overture.

Green's personal notes also list several unused thematic sequences

considered for the "Overture," including the "Swamp

Agitato," "The Carriage Ride," a "War Commentary"

theme, and an "Emotional Tension" subject. At one point

Green also notes: "Call Sendry May 4th with 'Never' development".

The first

actual cue in the film (after the Main Title song slowly fades

out over a series of establishing landscape scenes) is "Nell

and Johnny's Graduation Gifts," built mostly on transformations

of the optimistic motif that springs from a simple major chord

in the second inversion, but given a modernistic cast with its

prominent use of major 4th intervals.

The instrumentation is marked: 2 fl.; 1 ob-E.H. (English horn);

2 cls. (A & B-flat); 1 bass cl. (3rd cl if wanted); 1 bn;

3 hrns' 1 harmonica' 1 perc- triangle; bells; 1 hp' 1 cel; 14;

4; 4; 2 (these latter numbers referring to the string section):

total instruments: 38. This cue appears on the album almost exactly

as it is heard in the film, underscoring the sequence in which

Johnny and his Raintree County sweetheart, Nell, exchange graduation

gifts in a sunny woods. Like most of Green's cues in his personal

volumes, this one is notated in the seven stave format he described

above; his notes to his orchestrator (here unspecified), are

included. For a shot of Nell crossing the stream, Green suggests:

"This is now a rich flowing pastoral - string-lead tutti

- warm with shimmering wws (woodwinds), fluid harp, etc, the

soft bells, celeste, etc." When Nell presents Johnny with

his gift of a book on Raintree County Green notes: "This

is a straightforward statement of the Raintree song. The melodic

burden to be entirely with the strings - Completely simple

- dialogue style." (A harmonica solo nonetheless

captures and elaborates the already poignant melody.) As Johnny

and Nell exchange an emotionally charged glance, Green explicates:

"This is a big string lead tutti - the big open country

- much warmth - pastoral style, wws. perhaps - but don't cover

the tune!". That so subtle an exchange as that of mere glances

should elicit from Green so pointed and precise a musical response,

points to that incredible symbiosis between music and emotion

that Hollywood in this period (and Green uniquely in this instance)

inherited from the legacy of European romanticism. No date is

attached to this "Johnny/Nell" cue.

Reel 2, Part 2": "There's Another Tree"

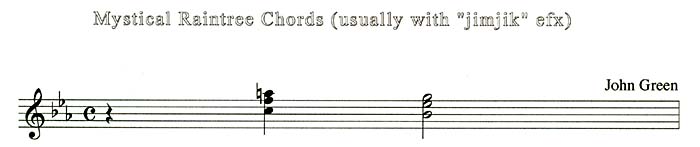

The next cue is a brief but evocative track, "There's Another Tree," (not heard on the soundtrack album). It underscores the Professor's description of the mystical Golden Raintree which, local legend holds, Johnny Appleseed brought to the heart of frontier Indiana (interestingly, the idea presented here is essentially that expressed on the back of the paperback edition: a lovely Americana myth that gilds the novel's tortured psychologies with a homegrown transcendent grandeur). Scored for 2 flutes (1 doubling alto flute), 1 oboe, 2 clarinets, 1 bsn., horns (Green's asks "2 or 3, Al?' suggesting Albert Sendrey or Alexander Courage worked on these sections), 3 percussion: bells, xylophone, vibraphone, and "small cymbal-metal rod" and a note with "finger cymbals" crossed out and replaced by" "Raintree Jimjik," 1 harp, 1 celeste, strings: 14, 4, 4, 2. (No total here). "Echo Chamber" is also written and double-underlined on the title page. The cue is an exotic, mystical variation on the title song, scored for highly reverbed (and atmospheric) alto flute solo and tremolo strings divided in three and four parts, which vividly underscores the Professor's narrative (including a "chinoiserie" spin on the bridge) about the oriental origins of Appleseed's planting. Needless to say, the cue sublimely tracks the profound feelings that the Raintree and its attendant symbolism arouse in the questing Johnny. Date: 5/3/57.

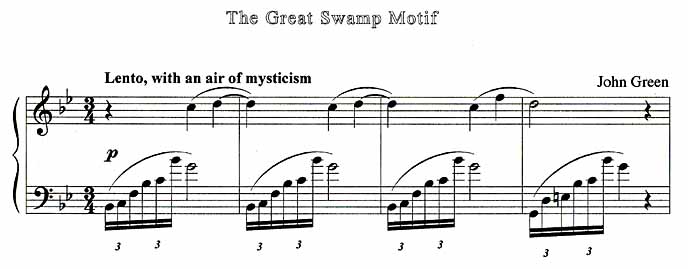

Reel 2, Part 2: "Johnny's Search For The Raintree"

The Professor's provocative narrative leads directly to "Johnny's

Search For the Raintree," one of the most ecstatic and pantheistic

sections of the score, and one of the film's most celebrated

cues. The orchestra is expanded here, mostly by a full 4/3/3/1

brass section, along with additional percussion including 4 timpani.

Green notes that the "Raintree Jimjik will be separately

recorded," as will be 6 high soprano voices. Strings are

also expanded (22/6/6/4), bringing the orchestra to a total of

64.

Titled simply

"The Swamp" in Green's score, the cue is a contrapuntal

fusion of all the motifs heard in the score so far, including

hints of the "Nell and Johnny" theme (suggesting that

their love may already be the answer to Johnny's youthful search)

and introduces new material in the form of the mystical motif

of the great Swamp itself, a combination of an ascending bass

arpeggio preluding the mystical half-step swamp motive (C-D)

heard almost immediately in the unison female voices.

A fragment of the Raintree song, its opening perfect 5ths, is

heard in solo horn (marked "hauntingly" at measure

6) as the swamp motif extends itself in triplet figures in 4/4

and 3/4 while the accompaniment remains in 12/8 and 9/8. As the

wordless voices soar to a high obligato (measure 11) the full

melody of the song is heard in the cello section in a high register

as the vocal obligato continues, escalating from unison to thirds,

and finally to ecstatic full triads at the "mystic"

parallel chords which always form the transition to the song's

bridge.

At measure

22 the voices revert to unison for a statement of the bridge,

but a series of abrupt and rather jagged cuts on the soundtrack

of the film suggest that there was some last minute tampering

with the visual structure of this sequence. In the film the 4-part

horn chord at measure 21 is repeated, an obvious and rather awkward

studio edit, and a large and quite abrupt cut (which includes

the end of the bridge and the reverbed trombone reprise of the

song's main melody with its lovely solo violin and harmonica

counter lines) is made to measure 28, the "Subito molto

agitato" section where Johnny falls into a hidden pool.

Cuts continue in the film music track, including some measures

dropped out of the agitato fugato treatment of the song melody

underscoring Johnny's struggle in the water, and some bars are

also snipped from the beautiful transitional coda, with its reprise

of the swamp motif heard in solo oboe as the mystical voices

"ahhhh" the "Song of Raintree County" to

bring the sequence to an unexpectedly tranquil close.

Fortunately,

the cue as Green composed it is heard in its entirety on the

soundtrack album. That there were some problems with this sequence

during the post-production period is also suggested by the fact

that Green's score has an insert (noted as measures 27a to 27g)

with a crossed-out measure at the end. Though no arranger credit

or date is included with Green's sketch, a somewhat smudged comment

at the "agitato" section at measure 28 states: "Al,

please add no preparation, wws. (?), hp. gliss. or the like.

The complete shock is the intent here". At the same point

(where Johnny falls into the pool in the film) Green notes the

sopranos' climactic high B-flat as "Quasi scream"!

While up

to this point the film is promisingly engaging, due primarily

to idyllic location shooting in the Nell and Johnny scenes, and

especially to the cynically witty dialogue and arch characterization

of Nigel Patrick as the Professor, the swamp sequence, with its

picturesque but sadly mundane imagery - at one point Green notes

the "big bird shot" in his score - is something of

a let-down. Nothing in the literal visualization of this sequence

measures up to the poetry with which Ross Lockridge, Jr. evoked

the mystical pantheism of his mythic Raintree County, or indeed

to the very Lockridgian music which Green created for this key

sequence. (Which is no doubt why the sequence was ultimately

trimmed).

In the cinematic

"Raintree" director Dmytryk seems more successful with

actors, particularly the males, than with mood or atmosphere.

The swamp sequence, more than any other in the film, also suggests

that MGM got to "Raintree County" several years too

late: episodes such as this should have called forth the magical

poetic naturalism of such location/studio fusions as "The

Yearling" (not to mention the on-location naturalism that

director Clarence Brown and MGM brought to their unexpectedly

authoritative realization of Faulkner's "Intruder In The

Dust"), and of certain studio hot-house films like "The

Pirate" or sections of other musicals such as "Ziegfeld

Follies". The Swamp sequence would surely have benefited

from some of the studio poetry of the sequence from "The

Yearling" when Jody finds the fawn in an artfully artificial

Florida glade and carries it home against the backdrop of a luminous

MGM cyclorama of Maxfield Parish cloudscapes. But by the late

'50s even MGM had lost its ability to convincingly stylize the

lush, highly atmospheric studio look that found its apotheosis

in the 1940s (as films like "Raintree" and "Green

Mansions" sadly proved). Traces of this ambiance fleetingly

appear in "Raintree County," for example, in the New

Orleans episodes, some of which have the soft-focus mezzotinted

look of Minnelli's "Limehouse Blues" sequence in "Ziegfeld

Follies". The swamp cue is also undated.

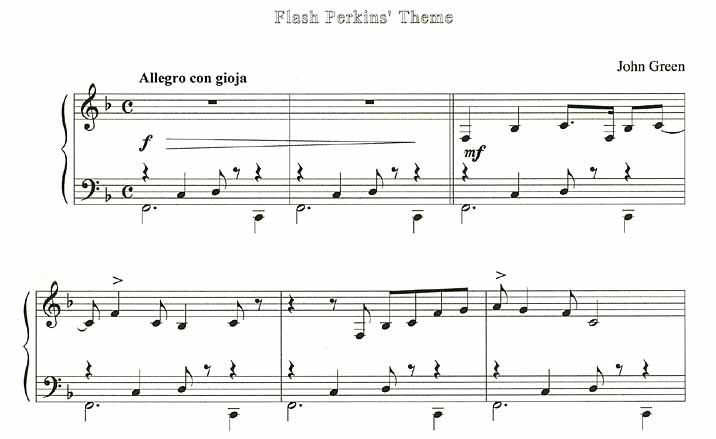

Reel 3, Parts 1 & 2: "Freehaven"/"Flash Perkins"

After a brief cue, "Nell and Gar", underscoring Johnny's post-swamp encounter with Nell and Garwood Jones (and cut from the final print), the scene shifts to the rural Indiana town of Freehaven, and a jaunty, folk-like motif for Flash Perkins, with its infectious banjo sound, and syncopated, pseudo ragtime rhythm.

Green's score includes two "Freehaven" cues, and it's

the second (G11), titled "Freehaven 2nd Revised," dated

7/30/57, and marked "Andantino alla Campagna," that

is heard in the film. The major cue in this section is "Meet

Flash and Susanna," dated 5/6/57, and which is introduced

by a brief "Prelude" (Reel 3, Part 2A, 5/13/57); both

underscore Johnny's meeting with Flash Perkins (Lee Marvin),

a bragging rake who challenges Johnny to a spontaneous footrace.

Green notes concerning the two opening cues: "This is a

direct seque-as-one at bar 2 from end of reel 3, part 2A - 'Prelude

to Meet Flash and Susanna'. Will be recorded as one piece."

Sections of this cue are heard as the "Flash Perkins"

record album track, but since the exciting musical build-up to

the race is abruptly cut off in the film when the Professor calls

a halt and reschedules it for the 4th of July, a climactic alternative

ending was written for the soundtrack album, and is included

in Green's score. The episode also introduces Susanna, whom Johnny

briefly glimpses as a crowd gathers for the race, the first brief

statement of their main love theme being intercut into the "Flash"

music (but not included on the albums). On the title page of

"Meet Flash and Susanna" Green notes: "Clarinetists

in this piece must be 2 of our jazz men" and "Please

get Jack Marshall on banjo (tenor). He will need capo."

A brief undated cue, "Johnny's Crown" (Reel 3, Part

4, and marked "Allegro rimato - sardonically"), concludes

the outdoor Freehaven sequences.

Reel 4, Parts 1 & 2: "Johnny and Susanna's First Meeting"

Reel 4 opens with Johnny's visit to the photographer's studio

where he first meets Susanna Drake. The score here is divided

into five cues, including two inserts in addition to the main

cues, with the pivotal cue being "First Meeting", Reel

4, Part 1. (These various cues are edited into the track "Johnny

and Susanna's First Meeting" on the album.) Only the opening

and closing cues in Green's volume are dated: 5/13/57 and 5/14/57,

respectively. The orchestration is for a reduced orchestra of

about 38 with an emphasis on strings and reeds. The scherzo-like

cue "Look at the Birdie" opens reel 4, cut off midway

by an "Insert" which interjects a fully-developed statement

of the "positive" love theme at measure 8 as Johnny

sees Susanna being photographed as she poses in a draped white

Greek gown, clutching a lily, and looking drop-dead gorgeous.

Liz gives the first in a series of marvelously unspontaneous

shrieks as she notices Johnny and rushes off to change. The lyrical

love theme is interrupted by a light scherzo variation as Susanna

is seen hurriedly changing so she can catch up with Johnny, and

the cue fades as he reluctantly leaves the studio.

Just as

Johnny is exiting Susanna rushes out to meet him (Liz shrieking

"Wait for me!" in another "unladylike" outcry

which is referred to in the ensuing dialogue), and the main cue,

"First Meeting", commences. This is primarily a development

of the love theme, pure and simple. At one point Green notes:

"Al: this next section is a simple, tender, warm and straightforward

statement of the Susanna-Johnny Happy Love Theme. The melodic

and harmonic burden is to be entirely in the warm strings unless

otherwise specifically indicated. Please add no element, harmonic,

rhythmic or linear that does not appear here. Do not spread any

counter element so as to place it above the top of the melody

line. We are behind dialogue all the way!!! Please indicate

in this sketch exactly who's playing what as you score!!!"

As with the "Johnny's Search" cue, there seems to have

been some re-editing of the film sequence. There is an alternate

bar at measure 25, succeeded by several deleted measures and

an added cue, "First Meeting (Insert)" The insert brings

the cue to a momentary conclusion in tandem with the Professor's

line, "Boy, you are definitely ready to graduate!",

when he sees Susanna on Johnny's arm. There also appears to be

an unspecified cut of an entire page at measure 29, and around

measure 35 Green notes "DO NOT COPY - THIS IS A DELETION

- AN ERROR -NOT A CUT!!!," after which the cue more or less

proceeds as notated, moving on to the statement of the "Happy

Love Theme" Green described above.

The cue

also includes a lovely but vaguely troubled variation on the

love theme, harmonized in open 5ths and 6ths, which lends an

appropriate premonition of melancholy to the cue as a whole.

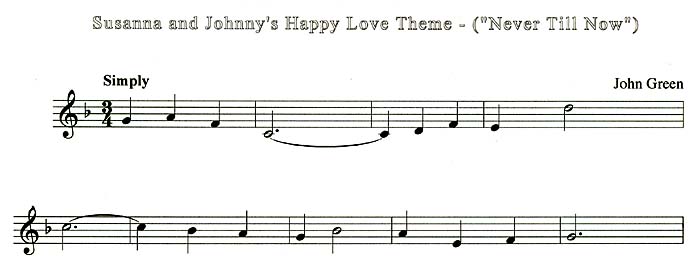

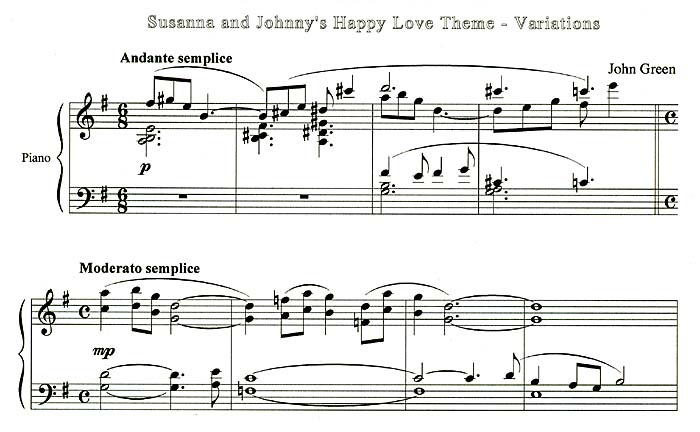

There are actually two variants of "happy" love theme

used throughout the score. The first is a languid, semi-pastoral

version in 6/8 time with slight harmonic variations. The second

variant is the one described above, in 4/4 with the opening motif

harmonized in 5ths and 6ths and slightly extended and developed.

Reel 4 ends with a brief coda, Nell's Huff," in which,

seeing Johnny with Susanna, she displaces her anger and slaps

Garwood; his stunned reaction is Mickey-Moused with comic muted

trumpets, in Green's words: "Harmon" (a type of brass

mute) "but not jazzy".

The ensuing

sequence involving the 4th of July footrace, and the Professor's

unsuccessful plot to get Flash Perkins drunk and keep Johnny

sober by surreptitiously substituting tea in Johnny's bourbon

bottle, opens with a close-up of the winner's wreath of oak leaves

(referred to in the "Johnny's Crown" cue) held by Susanna.

The footrace episode is one of the book's more celebrated passages,

and was reprinted in "Life" magazine at the time of

the novel's publication. The entire sequence is unscored except

for a few instances of source band music in the background (and

another great outcry from Liz as a firecracker is exploded near

her hoopskirt in the opening shot). Even the footrace itself,

so vividly evoked in the "Flash Perkins" album cue,

goes unscored.

Reel 5, Parts 4-6; Reel 6, Parts 1-4: "July Picnic"/"Train From The South"

The "July Picnic" sequence (along with its emotionally

charged "coda") is perhaps the peak of Green's by turns

heroic, by turns wrenching, lyricism. It heartbreakingly distills

both the idealistic aspirations of the American "experiment"

(which Lockridge's entire book throws into hopeful/despairing

relief), and that mid-summer sense of emotional ripeness and

decay which Johnny and Susanna's romantic peak-and-subsequent-downfall

so inexorably illustrates. Perhaps only Franz Waxman's underscoring

for the same holiday in "Peyton Place" is Green's equal

in both celebrating and mourning the day's unique mood of promise

and defeat.

After John

wins the footrace, the scene shifts to the streamside Independence

Day picnic of John, Susanna, the Professor, and Lydia Grey (the

beautiful but married object of the Professor's affections).

Green makes up for the absence of music in the preceding footrace

sequence by providing uninterrupted scoring for the entire picnic

scene, and its ensuing sequence, Johnny's later encounter with

Nell after Susanna has left Freehaven. Two short additional cues

support the concluding episodes which document the aftermath

of the Professor's botched attempt to escape Raintree County

with Lydia Grey. The picnic sequence is divided into several

cues - "Pursuit of Happiness," (no date), "July

Swim," (5/14/57), "Tell Me About the Raintree"

(no date) - all underscoring the sequence which climaxes with

Susanna's seduction of Johnny, while the "Dell Insert,"

(7/1/57) and "Your Exact Location" (no date) cue John's

brief but emotional reunion with Nell after Susanna has returned

to the South. All of these cues are heard intact in the 6.01

"July Picnic" track on the album.

"Pursuit"

is a brief introductory cue for the picnic scene, and a scherzo-like,

syncopated variation on the happy love theme which develops to

a swirling climax as Johnny and Susanna frolic in the stream

and collapse in a secluded spot on the bank. When Susanna asks

about the Raintree, (in one of Taylor's most subdued and touching

moments), Green supplies an equally moving variation on the title

song with contrapuntal lines for harmonica and the wordless female

choir heard in the swamp sequence: "Tell Me About The Raintree".

As Johnny and Susanna passionately embrace, the music peaks over

a discreet fadeout, continuing uninterruptedly as the scene shifts

to Johnny and Nell in the fields, with an ecstatic development

of the Johnny/Nell motif in solo trumpet and strings. Green again

noted his desired effect: "Again the big open pastoral quality

as in Reel 1, Part 2 - the upper woodwinds moving around the

inner harmony. The two harps and celeste helping the float and

shimmer continually." He further adds humorously: "immer

der schimmer, toujours la schmour" and "sempre I spaghetti,"

adding on page 143, "relax the flax." John's conversation

with Nell, "Dell Insert," as he speculates on becoming

a great writer, effects a moody antiphonal development of their

motif, fused with the "Raintree" song theme, and the

cue concludes with another full-length variation on the title

song as Johnny and Nell temporarily reconcile: "Your Exact

Location". With these several cues contained in one continuous

flow of music, one is struck by Green's impressive skill at both

developing his motifs in a cohesive, dramatically compelling

fashion, and deftly integrating appropriate and highly atmospheric

variations on the resilient title tune into the underscore.

Several

brief cues (all undated)--"Going Home" (Reel 6, Part

3), which is also found in the revised version heard in the film

(Reel 6, Part 3A), and "Train From the South" (Reel

6, Part 4, here arranged by Alexander Courage)--provide hints

of the polytonal brass chords, some built on 4ths, which will

characterize several of the later Deep South/Civil War cues.

The brief brass "Train" cue, also marks the end of

the film's first section, and the symbolic end of Johnny's youth.

As the train on which the Professor finally escapes pulls away,

he bestows on Johnny his richly cynical last word, with this

departing comment: "Dear friends, remember me as someone

who loves Raintree County, but just happens to loathe everyone

in it," at which point Johnny finds Susanna on the platform,

newly returned from the South with the news that she is pregnant.

The Rest of the Score

While this opening third features some of Green's most charismatic

and lyrical music, his score continues to grow in power as the

screenplay moves into its long-in-coming (and somewhat laborious)

resolution, maintaining a consistency and depth that unfortunately

eludes the rest of the film. Space prohibits further cue-by-cue

discussion of this wonderful American musical classic, but mention

should be made of Green's highly original music for the gradual

manifestation of Susanna's dementia, as well as his haunting

(and haunted) cues for the sequence in which John and Susanna

visit the burned-out shell of her childhood mansion where she

formed a deep and lasting attachment to her Negro nurse, Henrietta.

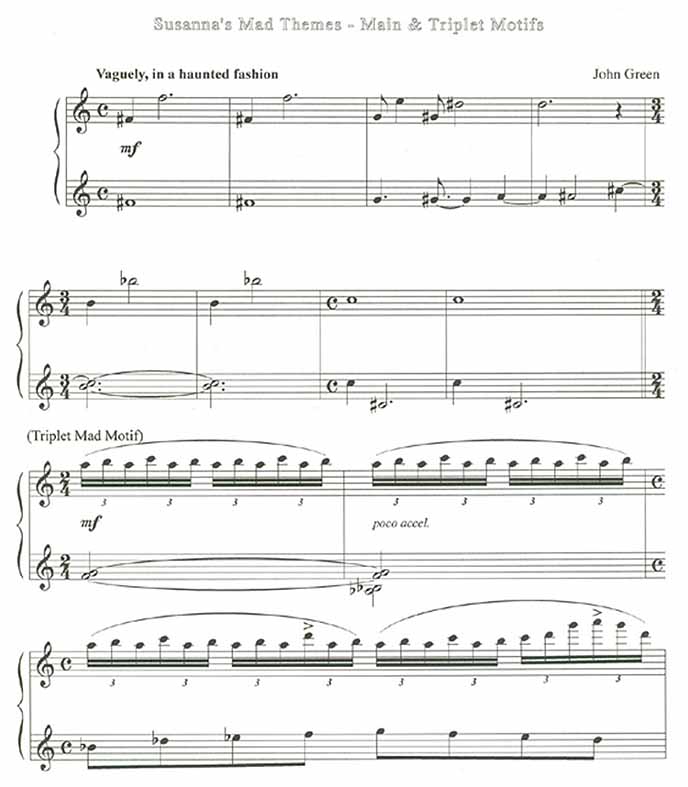

Green uses

a motif based on the expressionistic interval of F-sharp

to F-natural, sometime B-natural to B-flat, and first

heard on an anachronistic but oddly appropriate alto sax (with

added reverb effect) to represent Susanna's madness. There is

also a more agitated secondary "mad" motif of 16th

note triplets which whirl over a counter melody based on

a whole-tone scale. (See "Triplet Mad Motif").

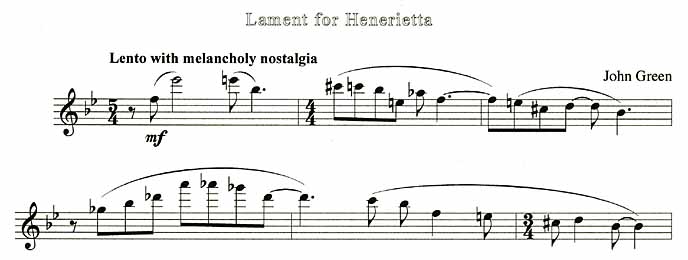

The ethereally melancholy "Lament for Henrietta," heard as Susanna describes her tormented childhood, begins with a hint of the same interval, suggesting the connection between Susanna's condition and her conflicted attachment to the black woman who took the place of her also mentally disturbed biological mother, and with whom her father was having an affair. This lovely melody is first heard in solo flute, also with dreamy reverb, and later in full strings.

As the film moves from its opening sequences in the mythic Indiana

of the hero's youth, to his coming of age in the Civil War and

a disturbing marriage which ends in Susanna's (rather contrived)

death, Green's score accordingly develops in depth and complexity.

The orchestration, ably realized by Green's staff of six assistants,

is relatively traditional, with an emphasis on strings and a

well-utilized reed section, and an escalating use of brass in

the latter sequences. But along with this basic instrumentation,

the modernist tone of Lockridge's novel is also evoked by the

use of modern recording technology.

Most obvious

is the aural motif for the Golden Raintree, an electronically-concocted

shimmer of bells, notated by a cymbal-style "X" with

an ensuing downward glissando sign in the score. This sound,

which Green arbitrarily named the "Jimjik" - "the

equivalent of 'thing-a-ma-bob,' merely an identifying handle"

- was separately recorded and given its own channel in the final

mix (when it was added to the previously-recorded orchestral

tracks), and is just one example of the forward-looking recording

techniques that make "Raintree" an early masterpiece

of multi-track studio scoring and overdubbing. Green described

the mechanics of the effect and its technological application

within the score: "A good toy glockenspiel, scraped from

top to bottom by two pairs of brushes (one pair following the

other - two percussionists, of course) produced the effect. On

the recording stage, to the naked ear, it was virtually inaudible.

It achieves the characteristic heard on the sound track via multi

magnification and maximum reverberation (echo chamber). The exact

method of producing it was later worked out by trial and error

on the recording stage." 12 The "Jimjik"

effect is usually heard to the mystical parallel triads heard

between the first (A) section of the "Song of Raintree County"

and its bridge (B).

The score's technological aspects are particularly notable in

the Southern sequences when Susanna's dementia begins to escalate,

notably in the eerily nostalgic "Burned-Out Mansion"

cue, made-up of several individually recorded takes - male voices

and banjo, a plantation polka for strings, and a basic orchestral

track - all of which was superimposed on tape (to click tracks

carefully indicated in the score with mathematical precision).

Electronic enhancement also evokes the frankly mystical elements

in the film's first third: the reverberated voices in "Johnny's

Search For The Raintree," and the similarly enhanced harmonica,

female voices, and sensuous alto flute in the "July Picnic"

cues. Green's technical notations - "alto sax, pure tone

in echo chamber" - are an integral part of his detailed

orchestral sketches.

Green touched

upon of the mysteries of studio composing and recording which

are such an integral part of the total "Raintree" sound

in a reference to the motif for Susanna's favorite doll, Jeemie,

a motif closely related to her dementia music: "The doll

motif, recorded as a separate entity, was composed and orchestrally

arranged in such as manner as to be played against the basic

Mad Theme during the re-recording or dubbing process. In other

words, that which emerges on the sound track as a single piece

of contrapuntal music, was never played as such on the recording

stage. The arithmetical niceties of timing, meter, and the like

are sufficiently intricate to form the basis of a separate article."

13

Some

of the complexities of the process can be seen in a description

of the collaboration between composer and sound engineer involved

in creating one of the brief (2.21) doll cues made up of two

separately recorded tracks overdubbed to play back simultaneously,

(as Green described above). For "Where Is That Doll"

(reel 12, parts 3 and 3X, , or numbers G51 and G52 in Green's

personal score), Green explored both the technical and psychological

aspects of his music and motifs in a note to recording engineer

Bill Steinkamp: "This piece (G52) works along with the basic

music track (G51) starting and ending as above indicated. This

is the doll motif and works in and out (of G51) as a kind of

a 'sick haze' - barely heard, yet there. We first become

aware of it when Susanna says, 'Where is that doll?' As Johnny

says, 'Come to bed' - we loose it. As she says, 'No, I must find

it,' it somehow is there again, having started to sneak in on

the second of the two 'no's' that precede the complete sentence.

As Johnny says, 'Don't you remember, etc.' it's gone again. In

the silence following Johnny's '.... a long time ago'

it is heard a couple more times, and is gone as J. puts

arm around Susanna to lead her away." Green's note concludes

with an emphatic comment on balance: "At no time is this

track as loud as the track it is running against!!!" Detailed

timings are attched to the notes for these cues, as they are

for most of the cues in Green's first volume: 0:20, Susanna:

"Where is that doll?", 0:50, Johnny puts arm around

Su to lead her, etc.

In his "Film/TV

Music" article Green cited Steinkamp and his contributions

to the score: "Any discussion of the music score of 'Raintree

County' would be incomplete without enthusiastic thanks to the

artist who was at the electronic controls during the re-recording

process, William Steinkamp. It is his masterful combining of

all the sound elements of the picture that brings the music to

its completed state on the sound track." All of which reveals

how the composer consummately merged a lyrical and essentially

traditional style with "modernist" elements, both stylistic

and complexly technical, to vividly mirror Lockridge's wildly

ambitious literary fusion of the same dissonant perspectives.

Ultimately, Green's magisterial score, with its free-floating,

perceptive intermeshing of character and emotional leit motifs,

is, in fact, the only element in the film that genuinely reflects

and pays homage to Lockridge's immensely poignant, homegrown

adaptation of Joyce's Olympian stream-of-consciousness meditation

on mundane reality.

Larry Lockridge

also commented on the score in a letter to the writer: "Green

should have won the Academy Award for the 'Raintree County' score,

but the movie itself probably killed his chances. I still remember

the thrill I felt as a kid hearing that score before seeing the

movie. If only the movie had been the score's equal! I met Green

at the premiere in Louisville (when he was still 'Johnny'), and

again many years later here in New York, where some of his music,

including portions of the RC score, were performed at Carnegie

Hall. It is odd, but true, as you say, that despite the movie's

badness a sort of charisma attaches to it. Green thought his

score his own best work." In the same letter Lockridge also

noted the possibility of a new dramatization of "Raintree"

as a TV mini-series. 14

In

response to a letter written to Green long before the recognition

of film music had become fashionable among both fans and academics,

the composer himself wrote to the author of this article:

John Green

10 Vicarage Gardens

London WS England

24 March 1968My dear Mr. Care -

"I am deeply grateful for your extravagant compliments about my RAINTREE COUNTY score, and I am amazed and delighted by the detailed knowledge of the score that your compliments reflect. I was particularly gratified that your favourite spots in the score include several of mine.

Your references to aesthetic reward or lack of same in connection with the writing of film music triggers so large a topic as to rule out discussion in a letter of this kind.

Your reference to the hit songs that I wrote prior to composing the score for RAINTREE leads me to tell you that a large part of my professional life has been spent in the making of music of all kind for films. I started as a rehearsal pianist at Paramount in December of 1929, at the age of just 21.